Our breakup made headlines in Le Monde and Le Figaro. We sold the apartment on Rue Passy. Brigitte moved to St. Tropez and started her foundation and I, heartbroken and heavily in debt, rented a little fisherman's cottage in Ravelo, on the Amalfi coast. I was sure it was going to be the toughest summer of my life. I had no idea I was being set-up when a friend invited me to a dinner party and I found myself seated next to Italy's hottest adult film star. Chi-chi and I hit it off immediately. We rode through the night in her white Dino and stayed in her Milano flat for a couple weeks, leaving the bed only for food, drink, provisions. We melded beautifully. Then came the work call she'd been waiting for. We moved into a '50s two-bedroom home with a pool off Laurel Canyon. Chi-chi knew she was onto something big. It was not easy to watch her go off to work everyday with men twice, three times my size. But I was a believer.

The Holy Fuckness of It All, 2

The Holy Fuckness of It All, 1

We started off so blissfully, the wine, the cigarettes, the terrific sex. Then came that first stray mutt. Then Sandrine, a lost tabby. Then litters of cats and dogs, a $15K donation to WWF, a three-month trip to Nairobi to rescue a wounded giraffe. I was hoping for a son. She was mothering quadrupeds.

Shards of Broken Dreams (or, Pieces of a Man’s Memoir, The Drunk Tapes)

On a Heathrow-JFK flight in 1990, three beers in, The Replacements “Tim” on my mustard yellow Walkman, the neither-here-nor-thereness of 35,000 feet loosening things, a ball point pen and a Spiral notebook spread out in front of me to catch what drops.

The song “Waitress in the Sky” comes on and suddenly I’m looking at the Pan Am stewardess with a sideways grin. Then the lyrics: “Sanitation expert, maintenance engineer, garbage man, janitor, and you, my dear”.

That writing could do this, by association belittle, poetically, was a revelation to me. What if, for instance, the lyrics went, “Marilyns, Mother Theresas, Madonnas, and you, my dear,” what would that say?

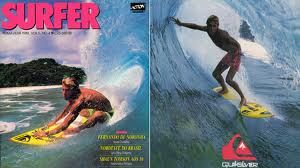

The surf mags I pored over got less play. In their place: Henry Miller and Jean Cocteau and Burroughs and Ginsberg and Brautigan and Sarte. The patent-leather red Adidas I sported (‘rocked’ had yet to be coined) soon took on an air of superficiality, as did the logo-bedecked baseball caps and painstakingly mussed hairdo.

A recession, Kurt Cobain and Sonic Youth and J. Mascis, Rodney King riots in LA, a proliferation of coffee houses and open-mic nights, shaggy sweaters from thrift stores, an appreciation for the weathered over the shiny, the near-disappearance of cocaine, at least in my little world, and a whole lot of pot in its place—these things helped me to shake my pro surfing dream and open to something new.

Day of Days: Sam Shepard’s Long Ride

“I don’t own a fax machine or an answering service or a call forwarding or a cellular car phone or a word processor, and I’ve never volunteered for what they call ‘press junkets.’ On top of all this, I’m not getting any younger, and my face is falling apart. Most of my lower teeth were knocked out by a yearling colt in the spring of ’75. Half my upper teeth are badly discolored, and one of them’s been dead for as long as I can remember. When you get right down to it, I’m lucky to even have an agent at this point in time. I’ve been involved in many dangerous, foolish things over the years, more by accident than choice. I’ve been upside down under falling horses at a full gallop; I’ve been fired upon by a 12-gauge Ithaca over and under; I’ve rolled in a 1949 Plymouth Coupe, which is a hard car to flip over; and I almost blew myself up once with a plastic milk bottle full of white gas on the Bay of Fundy, where they have the highest tides in the world. Still, I would gladly go through all these dumb acts ten times over rather than get on an airplane of any kind. I admit to an overwhelming vertigo that I don’t quite understand and I’m unwilling to psychoanalyze. The absolutely realistic sensation of falling without end—that’s one I have no power over. Luckily, I love to drive, the farther the better. I love covering immense stretches in one leap—Memphis to New York City, Gallup to LA, Bismarck to Cody, leaps like these, without a partner, completely alone, relentless driving, driving till the body disappears, the legs fall off, the eyes bleed, the hands go numb, the mind shuts down, and then suddenly something new begins to appear.”

—Sam Shepard, from Stalking Himself, a 1998 PBS documentary

Unlike the violence and despair and spittle-laced soliloquies that are the hallmarks of his plays, Sam Shepard’s life has been blessed. Born in Illinois in 1943, Shepard moved often, following his father, a career man in the army, from base to base around the country. After a year at college he left home and toured as an actor with a Christian theatre troupe, the Bishop’s Company Repertory Players. At 19, in 1963, he moved to New York, fell in with a group of actors and playwrights who would comprise the Off-Off Broadway movement, and wrote one-act plays with ferocity. His work connected. Between 1966 and 1979 he won ten Obie Awards (given to Off Broadway plays). In 1979 he won a Pulitzer Prize for Buried Child, a play about the fragmentation of the American nuclear family. In 1980 he won an Obie for Sustained Achievement. In 2009 he received the PEN/Laura Pels International Foundation for Theater Award. In short, Shepard is one of America’s most important playwrights.

That’s not even to mention his acting. Strong jaw, dimpled chin, almond-shaped blue eyes, windswept dirty blond hair—Shepard exuded the solitude and vastness of the American West. He began his career in earnest when he was cast as the handsome land baron in Days of Heaven (1978), opposite Richard Gere and Brook Adams. A host of important roles followed, most notably his portrayal of Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff (1983), earning him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor. His achievements are endless. He collaborated with Bob Dylan on the song “Brownsville Girl.” He wrote the screenplay for the Wim Wenders film Paris, Texas. He and then girlfriend Patti Smith co-wrote the play Cowboy Mouth. He’s written several short-story collections. It goes on and on and on.

Shepard’s most recent play is Heartless. Like much of his work, it chronicles a family on the brink of collapse. Unlike much of his work, the cast is made up of four women, all of whom are insane in their own special way. It is set in Los Angeles, and features what may or may not be considered a suicide when one of the characters dives into the great abyss that is the San Fernando Valley.

I caught up with Shepard via cell phone. He was in his car, driving along what I imagined to be a two-lane highway flanked by red desert.

Who or what inspired you to become a writer?

I don’t think it was any one event or any one person; it was a reticulation of experience that compelled me to start writing. I wish I could say it was Samuel Beckett, or a specific childhood experience. But it was really an accumulative thing. I started off wanting to be an actor, but I didn’t like the audition process—having to get headshots and humiliate yourself—so I started writing as a result of my failure as an actor.

What was your upbringing like?

Semi-rural. Crazy, insane family. Father in the air force; mother an elementary school teacher. It was pretty run of the mill America.

Were there lots of books? What were you reading back then?

My dad wound up being a Spanish teacher. He spoke fluent Spanish and he was a Fulbright scholar as well, so there was a lot of Spanish influence: Lorca, Cervantes and things like that that were tangential to some of the stuff that I started to become interested in. My first theatrical experiences, if you want to call it that, were rodeo and flamenco dancing.

You moved to New York at the height of the ‘60s counterculture. What was that like?

Well, I was lucky enough to arrive right at the very beginning of Off-Off-Broadway—La Mama, [Caffé] Cino, Theater Genesis, Judson Poets’ Theater, and things like that were just starting upon my arrival. I hadn’t timed it that way or even known anything about it. It was just serendipity, coincidental. But it allowed me to do sort of off-the-cuff productions on a regular basis at any theater I chose. I started at Theater Genesis down on 2nd Avenue and St. Marks, because the guy who ran Theater Genesis, Ralph Cook, was the headwaiter at the Village Gate where I was a busboy. Almost all the waiters there were also actors—Kevin O’Connor and people like that.

Did jazz play a big influence?

Yeah, it certainly did. I was a busboy at one of the biggest jazz clubs in New York, the Village Gate, so I got to see Thelonious Monk, Gerry Mulligan, Dizzy Gillespie, you know, all those great bands. And the stand-up comic on the break in between bands was Woody Allen.

Did you have mentors at that time? Were there writers you were looking up to?

No, I was pretty much on my own. As a writer, of course Beckett always played a very big part, but I never met him personally—I wish I had.

I read in one of your interviews that you didn’t rewrite at that time—first thought, best thought.

Well, it used to go hand in hand with that old notion of improvisation, which I suppose was a jazz idea. At that time in the sixties there was a certain purity associated with it—which was kind of ridiculous—where you could do no wrong, where anything on the page was OK, you didn’t need to rethink it. So I had that sort of arrogant attitude about it, and later discovered that it was far from the truth about writing.

What about now, do you do a lot of revising?

Yeah, almost immediately when I finish a page I’m devouring the re-writing, I’m on it. I’m working on a book now so there’s this incredible scribbling on just about every page. It doesn’t mean that someone can’t just directly make a manuscript that’s impeccable, you know, like I’ve seen some of Cormac McCarthy’s pages and there’s not one correction on them, which is kind of amazing.

Do you write your first drafts longhand?

For the most part, yeah, but with this book I’m typing it, because it’s just simply faster. I’ve been typing my whole life so I’m very fast at it, and I love the feel of some of the typewriters I’ve got—mostly Olympias, they’re West German. It’s like a great Chevy. They’re very fast.

In New York you mentioned that you wrote Heartless pretty quickly, keeping sort of regular office hours.

The great thing about the Santa Fe Institute, where I’ve been working for the past couple years, is that it does have a formality about it. I show up around nine in the morning and work straight ahead until around noon, have some lunch, and then I usually work until about three or four in the afternoon. I get quite a bit done, whereas if I stay home I can write, but I don’t have that exterior, enforced discipline that I find at Santa Fe.

Tell me about the Santa Fe Institute.

I got a fellowship there a couple years ago on the recommendation of Valerie Plame Wilson and Cormac [McCarthy], I think. They were the two instrumental people in getting me this fellowship. So I thought I’d try it out and I liked it so much I asked if I could come back and they said ‘of course’ and they gave me a little corner of the library there and I’ve worked there pretty consistently. It’s composed 95% or more of scientists, so the people there are very interesting because they are working on, say, archeology, quantum physics, math, chemistry—just about every variety of science you can imagine. There’s never a lack of conversation. And it’s great not to talk to writers, to talk to people in another endeavor.

What do you read?

I read all kinds of stuff. There’s a book called Chaos, very scientific. I’m re-reading Lolita by Nabokov, which is amazing. I’m reading a lot of South Americans like César Aira and [Roberto] Bolaño. I usually read three or four, up to six books at a time. I’m reading this Japanese guy, [Haruki] Murakami. I like his short stories.

What are your days like? I’m imagining you spend a decent amount of time outdoors?

Well, I’ve got horses in Kentucky, but down here in New Mexico I’ve just got dogs. They like to hunt rabbits so we go out at night and chase rabbits (laughs). I grew up in a pretty rural area and I was always outdoors, it was always part of my makeup.

You write and you act. Do the two inform each other? Do they ever conflict?

I’ve never seen a conflict between the two of them. One of the reasons I started writing plays was because I had some minimal experience on stage and sort of understood the spatial, the time thing of it, what the experience of being an actor onstage was. So I felt I had a handle on theatre in a non-scholastic, non-academic, non-literary way, you know what I mean? I really understood what it was like to be an actor onstage facing an audience. I think that’s important. I think a playwright absolutely has to understand that it’s a dimensional thing, that it has to do with a live audience. No, I’ve never had any conflict between acting and film and writing short stories and plays.

Tell me about Heartless.

I’ve always had the feeling that a play should, for lack of a better word, write itself if you get out of its way. And this play sort of appeared to me, not to sound too hocus pocus about it. I had this notion of the heart transplant, and the sisters, and I desperately wanted to write something that featured women, which I haven’t done before. And so those were the essential elements that I started with, and then I was determined to let the play write itself and not try to constantly control it, which confuses a lot of people. But the audiences seem to dig it, the critics didn’t get it (laughs), but that’s OK.

What made you choose to set it in Los Angeles?

I was spending some time with a friend of mine in LA, and I can’t ever remember the name of that highway—it’s not Mulholland but it’s somewhere like that, where it’s kind of a rim, overall view over the entire city where you can in fact on a clear day see the ocean. Usually I’m kind of down in the city, so it gave me this incredible vantage point that I’d never seen before, and it started in places like that, where the main character, the old woman, sort of looks out over the abyss as she calls it (laughs). And then of course I grew up most of my childhood out in the Mojave Desert, so Los Angeles at that time in the fifties was a very exotic, distant place. I rarely came to it. I think I came once or twice with my great aunt as I remember, but it was always very exotic and distant. It was a place of the imagination, totally, as opposed to a nuts-and-bolts sidewalk place. Because I lived way out toward Indio (laughs).

I love your depiction of LA proper on one side and the valley on the other, and this edge or cliff that you could fall off. I grew up in the Valley. It took many years before I could admit that.

Yeah, right (laughs). But there’s something about the history of Los Angeles that just fascinates me, you know, this little pueblo that was sort of stimulated by this Irish mogul [William Mulholland] and his getting the water from the Owens River, and, you know, the whole Chinatown thing, which is probably largely fantasy but is taken to be fact. Where the water comes from, how this sort of desert pueblo turned into this monster is something you don’t even think about anymore. I find it really fascinating. And then Jedediah Smith…It’s a fantastic history.

Do you spend much time in LA?

No, I don’t. Whenever I’m there I feel this weird nostalgia mixed with terror (laughs). I feel like a part of me belongs there and another part of me definitely doesn’t.

Do you get much writing done when you’re in Los Angeles?

Yeah, I find it very inspirational in an odd way. For instance, I wrote a play called True West in Los Angeles, which is more or less based in the suburbs, but it is in LA. I wrote that entirely in LA and over a very intense period of time. I think I wrote it in less than a month. And it kind of fired on me I think more than anything because of the place. And there’s another play called Angel City, which is basically about LA but I didn’t write it there, I wrote it in San Francisco, which is odd. LA has continually played some kind of role in stuff that I’ve done, in fact it plays a part in the thing I’m writing right now.

Can you tell me about it?

Well, I’m reluctant to talk too much about it because I’m a little bit superstitious about talking too much about the things I’m working on. But it moves around two different characters and takes place in several different locations and has a kind of time thing about it. It’s a novella or a book, as opposed to a short story or a play. But I really find it difficult to talk about.

Hold Your Breath: Vava Ribeiro’s Deep Immersion into the North Shore

I first met Vava Ribeiro in 1996. We were in Amsterdam, covering the 9th Annual High Times Cannabis Cup. We both worked as journalists—he in Sao Paulo, me in Los Angeles. A mutual friend had given us vague physical descriptions and told us to look out for each other. In an airy banquet room, a bearded and tie-dyed commune founder gave a lecture about growing pot, dodging the man, and ballin’ old ladies. He paused often and at great length. The audience crowded around him, sitting Indian style on the floor, severely stoned. When the lecturer paused, shook his dreadlocked head, giggled, and said, “Sorry, I forgot what I was sayin’,” the audience hardly noticed. I can’t remember whether it was during this lecture or the one about hydroponics that an audience member raised his hand and pointed to the passed-out guy next to him. They exchanged a few words. The lecturer became flustered. “Is there a doctor in the house?” he asked. “Hey man, anyone know CPR?”

In any case, it was after one of these, a pack of stoned audience members stepping out into a bright corridor, that I saw a guy who fit the description. Brown-skinned, brown curly hair, big warm smile, two cameras dangling around neck, a girl, tall and beautiful, at his side.

“Vava?”

“Jamie?”

We’ve been great friends ever since.

Vava’s story goes something like this: The younger brother to two beautiful sisters, he grew up in the Gavea neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro, a short bike ride from Ipanema Beach, where sparkling waves and sunstruck tourists and G-stringed girls converged. Vava came to surfing at age thirteen. A goofyfoot with a smooth style and a dashing cutback, he swiftly climbed the Brazilian amateur ranks, a small village of trophies filling his mantle. When Rodrigo Mendes (son of bossa nova giant Sergio Mendes) started dating one of his sisters, the two became great pals. They surfed all day, partied all night, and obsessed over surf magazines in between.

Cut to a few years later. Rodrigo was living in New York, and Vava was enrolled at Rio’s Faculdade da Cidade, studying design. When Vava and his first ever girlfriend split up he was devastated. He booked a one-way ticket to France, with a brief stopover in New York. His plan was to surf himself into amnesia in the A-frame beachbreaks of Hossegor. He arrived at JFK and subwayed it over to Rodrigo’s downtown apartment. Rodrigo was in a frenzy. “Swell’s pumping!” he said. “Grab your board, we’re going to Jersey.” It was the last thing Vava expected to find in New York, but he went with it. For the next three days, he scored clean, overhead waves at Sea Girt and surrounding beaches. At night they ran wild in the East Village. Vava was hooked. He canceled his flight to France and stayed—for fifteen years.

The surf would never quite deliver the way it did for his arrival, but life certainly did. A resourceful man who speaks four languages and thrives in the presence of beautiful woman, Vava got a job assisting some of New York’s finest photographers. Within a year he was shooting his own stuff. Before long, his pictures were appearing in the biggest fashion magazines in the world. Vava traveled voraciously, spending time in Paris, London, Los Angeles, Sydney, Sao Paulo, and Amsterdam. In 2000 he won the photo competition at the prestigious Hyères Festival in France. Around that same time he began the body of work on display here. For the last decade, Vava has been immersed in “Hold Your Breath,” a book about Hawaii in general and the North Shore in particular. He grew up obsessing over the Hawaii depicted in surf magazines and movies. When he finally arrived there many years later, he found it to be both nothing and exactly like he’d expected.

What drew you to photography?

As long as I can remember I had a camera in my hand. I always knew that I was going to be doing something visual—an architect, or a designer, or a graphic designer. As a kid I was always doodling and doing little drawings and I was actually pretty good at it. When I got to college there was a photo class that I took and I loved it, and I felt good about it. My brother-in-law was a professional photographer. My grandfather was a photo-enthusiast; he always had a camera around. So photography was something that was familiar to me. I started shooting on my surfing travels. But I never set out to be a photographer—it was just a natural extension of my travels. But I really got the first buzz when I was in design school when I started to shoot and develop my film. At that time it was happening at a very subconscious level. I did not know I was going to become a professional photographer, but I got hooked then.

As long as I’ve known you traveling has been a huge part of your life. When we first met you had separate phone books for London, Paris, New York, Los Angeles, Sao Paulo, and Hawaii. Where did all your traveling start?

It started in the early ‘90s in Brazil. There was a very weird political scenario in the country itself. It was a very instinctive feeling that I wanted something else. I had traveled within Brazil and to Europe as a kid, with my family, and I knew there was something out there for me. I had no real plans for the future, I had a broken heart, I was bored at college, and I was tired of surfing in competition, and surfing itself. So all the main motors of my life weren’t fulfilling me at all. Once I started to travel it opened up this vortex, it opened up these possibilities. For me it was very easy to travel. I’ve always been very adaptable, very easy with new languages. Going to a new country and learning a different reality has always been exciting to me.

Did surfing contribute?

My very first international trip, alone without my family—I was seventeen years old—was a surf trip to Peru. We’re talking around 1988. And I was the youngest guy, I was with four other guys, all older, and we went to all the best places. We went to Punta Hermosa, we went to Machu Picchu, we surfed perfect Chicama. That was probably the gnarliest, craziest trip of my life. It was the first time that I heard about terrorists. There was a terrorist group in Peru. I knew there was going to be big waves, trouble, all the difficulties of traveling in South America. Peru at that time was a fucking shithole. But that didn’t stop me from going. I remember driving through Máncora, and Máncora was a dead town. It was year after El Niño, there was a mudslide that covered the whole town—all you could see was the roofs of the houses poking out of the mud. It was like a horror/western movie. You looked to the left and there was this crazy disaster, and you looked to the right and there were these peeling, perfect lefts with no one out, not a soul to be seen. We surfed our heads off. It was this wild contrast of joy and fear. Oh my god, this is amazing! Oh my god, where the fuck are we? At night they cut the power and we thought the terrorists were going to attack the town because that’s what they used to do: cut the power, attack the town, kill everybody, steal their passports, and move on. The Sendero Luminoso means “The Shining Path.” It was the biggest terrorist group in South America. They were pretty active throughout the ‘80s. When the power got cut everybody ran into the desert to hide, and we stayed in our little hut, and it turned out to be just a power shortage. We were shit scared. But that didn’t stop us. We kept on traveling through the desert. I think that planted the seed in me. The sensorial experience; the knowledge that I can function in whatever situation you throw at me—it made me feel special in a way. It made me feel good. Everything after that was easy.

What would be the highlight of your photography career?

In a professional sense we can talk about the prize I got in Hyeres, which was very renowned and opened up a lot of possibilities in my life. It gave me a little bit of status, but it also gave me the self-assurance and confidence that I needed. That was very fulfilling. But highlight of my photography career—that’s a tough question. How do you measure that?

You’ve been photographing the North Shore for over a decade. I remember us talking about how you grew up looking at pictures of Hawaii in the surf mags, and that your photos deal with how you imagined Hawaii to be, and what it actually looked and felt like.

My first trip to Hawaii was in ‘99/2000, so it’s been twelve years. A lot of the North Shore has changed. A lot in me has changed. Photography is amazing to me because after a while that file, that archive, has a life of its own. When something is about five to ten years old you start to look into the documentary value of it. The more it ages, the more significant it becomes. When I first started to photograph Hawaii the pictures looked like my dreams, or like the images I formulated in my head from reading all the surf magazines. It was like déjà vu. I realized at some point that just like my memories, the actual images I was shooting needed to age, to get some sort of ” real ” vintage value so they also could speak with that same tone as the images I was paying tribute to. And probably that’s why now these images make more sense then the first time around when I first stared to edit the work. Photography is a time travel platform. I wanted to portray my lifelong experience with surfing through emotional images. Hawaii was a place that could magnify that story and at the same time provide the elements for new theatrics. All I needed was to live them through a camera and let time do its part.

Is there a single image from your Hawaii work that you feel captures your impressions of the North Shore?

There’s an image of Jesse [Faen] with the Fish that I really like. He’s laying down in bed with the board next to him, and he’s raising his hand up to block the sun. It’s an introspective moment of a surfer. It has a vague narrative to it. It could have been me in that image. It could have resembled something that I saw in a surfing magazine when I was a kid. But it also resonates to the time that I was there hanging out with Jesse. There’s another picture where Joel Tudor is looking at me, and he’s wearing a T-shirt that says “Dora Lives.” That image could have been shot in the ‘70s or the ‘80s. When I shot that image then he was paying reference to something that I saw as a kid, of a place I only knew about through the magazines. Now I look at that image and think about first, the moment when I took the shot, and second, the period where I was a kid growing up with surf mags that featured the North Shore. There are two layers to it.

Who are your favorite photographers?

I can decipher my photography influences by layers. The portraiture of Richard Avedon, the colors of Stephen Shore, the haunting portraits of Emmet Gowin, the raw youth from Larry Clark, the skin and innocence on Jock Sturges, the cold and abstract compositions from Michael Schmidt. I’ve always been a photo junkie. I could name 100 photographers on that list. I also like movies. Strong visual narratives: Kurosawa, Kubrick, Antonioni, Lynch…

What makes a great image?

There’s no rationale to it. There’s no mathematical formula. There’s a distinct sense you get when you look at a good image. That’s the beauty of photography for me. It has to be felt. It’s not something that you see; it’s definitely something that you feel. It’s one of the most sensorial mediums that you could possibly have. The only thing I could possibly compare to it is music. You listen to it and you have a rush of thoughts and emotions and feelings. Photography does that to you. In a funny way, a good photograph will start a dialogue with you—internally you have this conversation going back and forth with the photograph. That to me is a buzz. That to me is what makes it so amazing. And another thing: photography as a medium is close to magic. A camera is an amazing, magical instrument. You’re recording a fraction of a second of a moment, and it stays. And you’re living that moment. And that moment is a whole different feeling when it’s frozen. This little machine does all that. What else do we have out there that is such a clever trick?

What are you most inspired by right now?

Music has always been important. I look at other people’s photography and painting. I try to draw inspiration everywhere. I could listen to a Silver Jews song, or Cro-Mags, or Vivaldi, or jazz and images come to my mind. If I close my eyes in darkness and listen to music my head creates images. Imagination is the most important thing in my head. Not creativity—that you can play with, or control in a way. But when you can access imagination and record that and bring that out—that’s the place where most of my work comes from.

FOR THE LOVE OF GEOFF DYER

There are several hundred reasons to love Geoff Dyer. One of them is his writing. The author of eleven books, including “But Beautiful,” “Out of Sheer Rage,” “Yoga For People Who Can’t Be Bothered To Do It,” and “Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi,” Dyer is hailed as a genre-defier. He explores, crosses lines. I want to say that he digresses, but in the astonishing rabbit holes down which he takes us, they don’t feel like digressions. In Dyer’s protean world, there’s no such thing.

I first met him a few months ago at a residency/workshop at Atlantic Center for the Arts in New Smyrna Beach, Florida. I was deeply enamored of him, which often leads me to stuttering and nervous, incoherent ramblings. Dyer put me at ease. He joked, he self-deprecated, he exuded a droll lightness. During a discussion about literature he said that he likes to think of writing books as epistemological journeys. Me being of the knuckle-dragging surfer variety, I had to look up “epistemological.” It means “the theory of knowledge, esp. with regard to its methods, validity, and scope.” Not only did this fire me up on my own writing (“Writing is an opportunity to learn in the public eye,” wrote another of my favorite writers), it made me realize what I love so much about Dyer’s non-fiction. He starts out on the bar stool next to you, drawing you in to whatever subject, and by the end of it your both dressed in cap and gown, clutching diplomas.

Another reason to love Geoff Dyer is his passion for balls. Dyer played tennis nearly every afternoon. His wins and losses became the source of inside, ongoing jokes that were bandied about the dinner table. One scorching afternoon we went to the beach. “How boring!” said Dyer, scanning the group of pasty writers stretched on towels, heads in books. He produced a tennis ball, and rallied us all into a game of catch at the shoreline. But ordinary catch was not enough for Dyer. “The idea is to fake each other out,” he said, eyeing me but rifling the ball to the unsuspecting player on his right. He also insisted we add an element of hot potato—the moment you catch the ball you’re already throwing it. Indelible memories of Dyer diving for balls in the spuming shorebreak, his drenched T-shirt clinging to his narrow frame, his toothy smile gleaming in the Florida sun. I felt nine years old again. Had he proposed we build a sandcastle I’d’ve been in without question.

“The Ongoing Moment,” Dyer’s illuminating discourse on photography, focuses on linked subjects, motifs, and gestures in his favorite images. He shows us how one picture leads to another, thus creating a sort of conversation between photographers like Paul Strand, Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, Edward Weston, and Robert Frank that, by extension, traces right up to the present.

Dyer and I spoke via Google Hangouts. He was framed dead center, cropped at the high forehead and lower chin, clean shaven, cheery, laughing easily. He was in New York, I was in LA, but it felt like we could have been sitting across the table from each other.

Q&A coming soon to Huck magazine—http://www.huckmagazine.com/

MASTURBATION IN PUBLIC (#3,796 in a series)

Last night I drank a bottle of Two-Buck-Chuck, masturbated first to Asa Akira while listening to Nine Inch Nails, then Like A Virgin-era Madonna while listening to The Smiths, felt lonely, a hole so big you could hurl into it Tonka trucks and puppy dogs and vodka shots and still not touch the sides, reached for Gmail/Instagram/Facebook/Twitter the way John Belushi must have reached for his syringe in Bungalow 3 on 3/5/82, wept for a whole bunch of reasons far bigger than my immediate pain, gorged on Ak-Mak sesame crackers and roasted red pepper hummus interspersed with spoonfuls of avocado and goat cheese, fell into bed with my clothes on — no teeth brushing.

Woke. Scribbled this entry into journal. Thought a lot about “creepy” and “oversharing” and “boundaries,” how these buzzwords produce shame for simply being human. Thought about posting this (honesty, tapping inner voice, shedding inhibitions makes a cloudy day sunny). Thought about not posting this (you’re a clown, who’ll take you seriously?). Thought, You’re sounding like Nicholas Cage in “Adaptation”...not only that, you start out writing about masturbating — now you’re masturbating in writing. Thought, Ah, fuck it.

GREAT FRIENDS

“What are you most proud of?” asked my therapist.

“Well,” I said — bulging passport, cutback in 1989, collage of female faces torqued in ecstasy. “I have great friends.”

“Beautiful. Care to elaborate?”

“Well, this one guy, Derek Hynd, he’s Australian, he’s in his mid-50s, and he’s an amazing character. He’s a writer—he was a pro surfer and he had a surfing accident and lost sight in one of his eyes, and he started doing a column in one of the surf magazines. His byline was a cycloptic eye, with ‘Hyndsight’ written under it. He’s a romantic, a fatalist. World War 3 could be going off and he’d be pointing out the pretty colors in the sky. He dances like no one you’ve ever seen, spasmodically, from pulses deep within. Almost like an epileptic fit. Oh, and he’s one of the best surfers in the world. And here’s the thing. He rides finless. Which, in surfing terms, is like surrendering all control, it’s like driving on ice, all traction is gone, so when he’s on a wave he drifts sideways, backwards, he twirls into 360s, he falls a lot.”

My therapist shifted, folded her hands together. “Do you feel finless, Jamie?”