Leanne Shapton on Pilgrim Radio

Becoming Westerly on The Advocate’s 15 Best LGBT Summer Reads

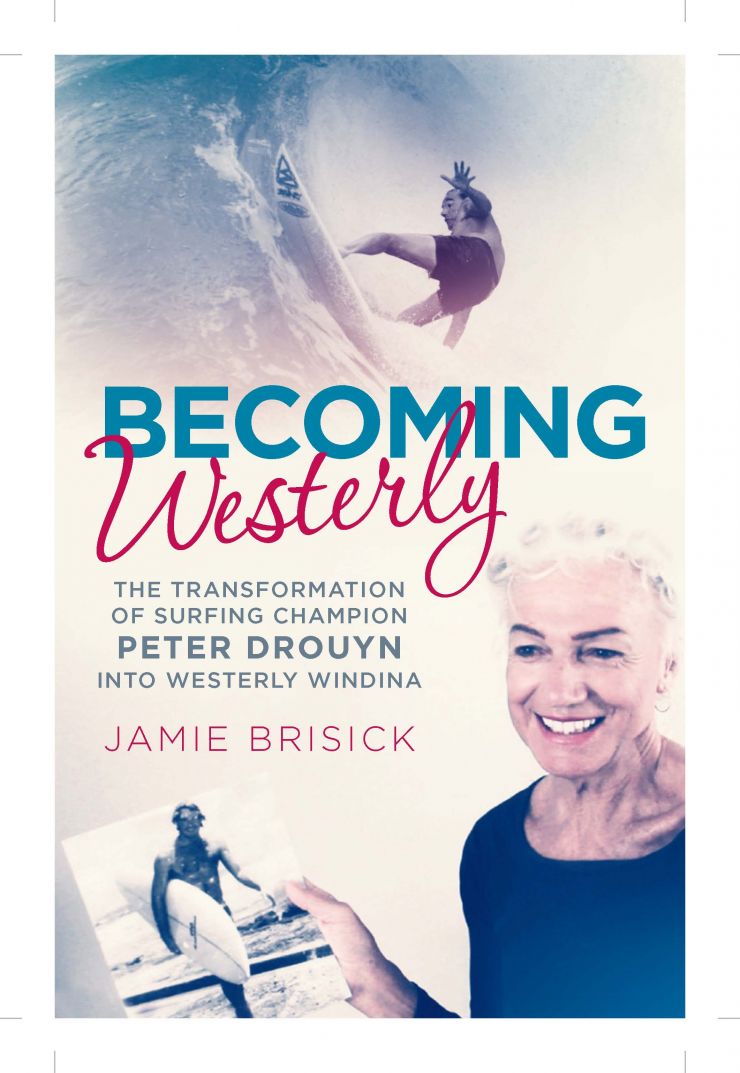

Becoming Westerly by Jamie Brisick (Outpost19)

Almost any athlete who comes out as trans right now will be compared to Bruce Jenner, but the story of surf champion Peter Drouyn’s odyssey from teenage Australian hopeful to 1960s surf champion to embittered has-been struggling to rise again as the glamorous, 64-year-old Westerly Windina is a story that deserves equal attention. As a surfer, Westerly pioneered an aggressive style called “power surfing,” introduced the man-on-man competition format, won the Australian National Titles, and brought surfing to the People’s Republic of China. But at the heart of that hypermasculinity lay an unhappy athlete who never felt properly credited. In the hands of journalist (and former pro surfer) Jamie Brisick, this biography is more than a trans coming-out narrative; it’s a story of a journalist chasing a legend and a woman trying to become the vision she’s had of her perfect self, raw and vulnerable but also wildly self-empowered after her 2012 gender affirmation surgery in Bangkok. (And if you’re too busy to read: Brisick’s U.S.-based documentary on Westerly, produced by House of Cards’ Beau Willimon, is scheduled for release this fall.)

Kem Nunn on Pilgrim Radio

Kassia Meador on Pilgrim Radio

Rhymes With Shove

Tom Carroll on Pilgrim Radio

Review: Becoming Westerly by Jamie Brisick Is The Best Surf Book Since MP’s

Review: Becoming Westerly by Jamie Brisick Is The Best Surf Book Since MP’s

24 FEB 201513,428 VIEWS

by Mike Jennings

Coastalwatch Surfing Editor

REVIEWS

From The Latest Issue of Surfing World, Out Now

By Mike Jennings

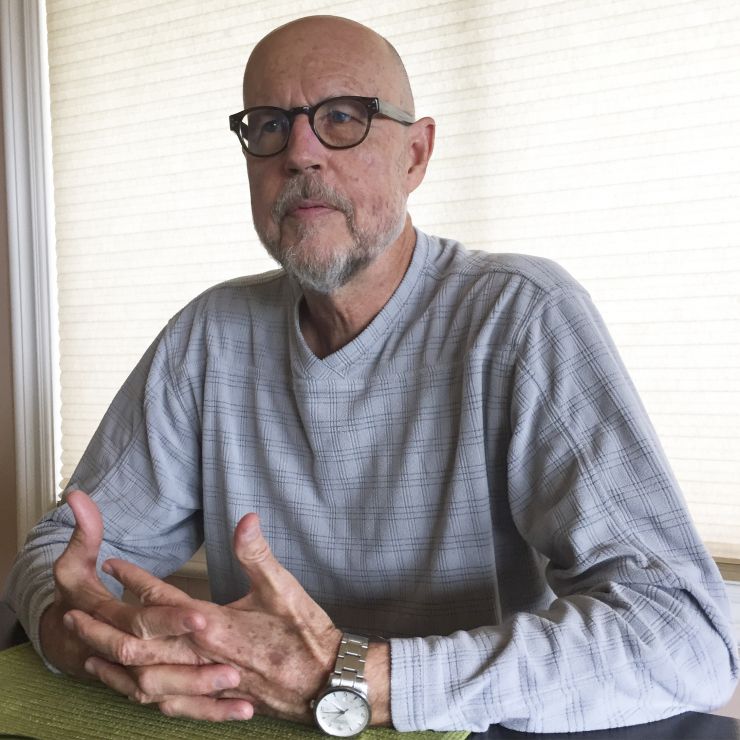

Peter Drouyn, 1970 Australian Champion, the first Australian Champion from Queensland, the 1970 winner of Makaha when said event was considered an unofficial World Title, the surfer who transitioned from the longboard to shortboard era better than nearly anyone, the revolutionary who invented the man on man competitive surfing format still used today, yes that Peter Drouyn has been on a dramatic physical and spiritual metamorphosis. From the hedonistic and handsomely brooding surfing champion, to the delicate Marilyn Monroe-like starlet, Westerly Windina. You’ve likely heard this story of Peter and Westerly. In surf magazines. Newspapers. ABC TV’s 7.30. Westerly even regularly contributes to this very magazine, but you haven’t heard the Westerly story like this. Not with the intimacy and detail and rolling prose that American writer and ex-professional surfer Jamie Brisick has gifted us in this biography, Becoming Westerly.

Brisick travelled to Australia in 2009 to write a 5000 word profile on Westerly for The Surfer’s Journal. What sparked there has, as Brisick says, “Swollen into the greatest love/hate relationship of my entire life…”. Following that profile Brisick and a world-class filmmaking team embarked on a documentary project about Peter’s transition into Westerly (which we should expect to see released in the next 12 months). It’s through that project that Brisick has likely spent more time and correspondence with Westerly than anyone that isn’t her immediate family. With her for all the big moments and a lot of little ones too, this book is a result of that time. But it is also so much more.

Becoming Westerly opens in a plane on the tarmac at Sydney, Westerly en route to Thailand for gender reassignment surgery. Writer and subject/friend sitting next to each other in uncomfortable economy airbus seats. Brisick is right there in the story whether he planned to be or not. Doting after her and her high-maintaining ways, he has to be a part of this story to tell it properly. Like On The Road’s Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarity, a character that shines so bright can only be explained through eyes burned by the glare. But Brisick brilliantly steers the story in and out of present day, weaving us through the fantastical surfing life of Peter Drouyn. Through the way Drouyn was failed by surfing but also how Drouyn, by his own grandiose ambitions and penchant for the sublime, forced surfing to fail him. Through his ambitions beyond a surfing career, introducing the sport to China and creating ideas for wavepools, the acting career in the UK. Through all of these incredible times that play a part in the ultimate re-emergence of Peter as Westerly in the surfing spotlight today.

Westerly and Peter are two of the greatest characters to ever grace surfing, two titanic life stories, and with Becoming Westerly Brisick has written incredible portraits of both. A story of the glory and terrible burden of ambition for greatness, and greatness unrecognised. Beautiful, sad, and full of hope, it’s the best book in surfing since Sean Doherty’s MP: The Life of Michael Peterson.

The Ultimate Survival Tool

At the time it was merely an extension of the wagons, Big Wheels, and bicycles that huddled in the corner of our garage, but now it’s a philosophical foundation, an ideology on four wheels.

I’m talking about my first skateboard: a 27” lime green Bahne with Chicago trucks and Cadillac wheels. Skateboarding came via cousin Jeff. I was eight, the youngest of three pinching and hair-pulling brothers. Jeff was thirteen, a surfer. His long blond hair was salt-matted, his T-shirts were raggedy, his Op corduroy shorts had holes in the butt from doing Berts, his heels and toes poked out of his Vans deck shoes. He rode a scuffed Logan Earth Ski with a Heineken beer logo glued to the bottom. He let us ride it down the sidewalk in front of our Encino Hills home. The pavement roared beneath our feet, sending something vital and electric through our little bodies. It had yet to reveal its outlaw, marginalized status, it had yet to send us to the hospital, but we could sense skateboarding’s danger. We liked that.

Bahnes were blade-thin fiberglass decks that flexed, producing a visceral connection to the pavement. Slaloming down Escalon Drive, I was an Olympian alpine skier in Hokkaido, I was Steve McQueen in On Any Sunday, I was Speed Racer, my favorite cartoon character, rounding a bend in his powerful Mach 5. I became one with the wood chips and the ivy and the gravel that scattered the sidewalk. I played games with myself: push, push, push as hard as you can up to the edge of the Sachs’s wrought iron fence, then glide—how far down the block can you go? I conquered fear.

We lived on a steep hill. About eight houses down was a side street that sloped upward. I’d zig and zag, with a little bit of figure eight, to shave off the speed, then, right around the Dash’s brown shingled home, I’d break into a low-tuck bomb, faster, faster, faster. Then I’d turn up the side street. The challenge was to begin the bomb from as far up the hill as possible. Once committed to bomb there was no getting out of bomb. Speed wobbles were scary. The pavement had teeth.

There was also a lot of just existential carving and kick turning down the block. Skateboarding was a place to dream. It awakened my inner life.

I started surfing in 1977. Skateboarding became a wave-riding surrogate. Every hedge was a tube, every driveway a sloping wall of water to pull an off the lip or cutback. By this time I’d gotten my first Dogtown skate. Somehow I’d discovered that Wes Humpston made those glorious boards that Jay Adams and Tony Alva rode. I found his phone number in the Yellow Pages. I phoned him up. I was eleven, my voice was high. “You a girl?” he asked. Fucken killed me. But I got a board—$20, big evil Dogtown cross on the bottom. It didn’t so much screech on the pavement as it tossed spray. Projecting, sublimating, creatively visualizing—this was at the heart of ‘70s skateboarding. I had a nose for crags and curves. Show me a city block and in two seconds I could show you a line, a series of ducks and weaves and carves and kick turns that was as personal as a fingerprint.

The best thing about skateboarding was that I did not need my skateboard to do it. In Pavlovian marvel, as if it had taken up residence in my bloodstream, I could be walking to the supermarket with Mom, all the while grinding curbs, slinging Berts, popping off little tree-root rises in the sidewalk and getting three, four, five inches of air. If I imagined it vividly enough, the physical sensations would arise.

I remember less the umpteen skateboards I owned through my teens, twenties, and thirties than the marks they’d leave on the wall. It was an ashen dual-wheel stutter, the street brought to that space next to the front door of wherever I was living. I remember something Thrasher editor Jake Phelps told me when I interviewed him for a book I was writing about the history of surf, skate, snow. “A skateboard is the ultimate survival tool. You can open a beer with it, use it to beat someone over the head, take it to a movie.”

In 2003 I was doing a manual wheelie down a street near NYU. It had just started drizzling; a fine mist covered the pavement. Ornette Coleman played on my Discman, the smell of pepperoni pizza floated from a corner pizzeria, I was Mark Gonzales circa Video Days when my rear wheels skittered out and I hit the ground with a thud. It took my wrist (my right wrist, my writing wrist, I had no health insurance) about six months to heal.

I’ve skated very little since. But I skate everyday. There’s a small bank on the corner of Essex and Grand on the Lower East Side that, in my mind, I have slashed off 500 times. There’s a sloping strip of Sunset Boulevard in Pacific Palisades that—don’t tell anyone—is a perfect snake run. It helps if you bank your turns in a super low crouch, dragging hands. I imagine myself wearing gloves.

Which is to say that skateboarding taught me imagination, i.e., survival and transcendence. It taught me how to repurpose the banal, urban landscape into a wonderland. It taught me how to live comfortably on the margins. It taught me that the best things in life are free. It taught me to listen to my own inner music.

*from Huck issue #48