At the time it was merely an extension of the wagons, Big Wheels, and bicycles that huddled in the corner of our garage, but now it’s a philosophical foundation, an ideology on four wheels.

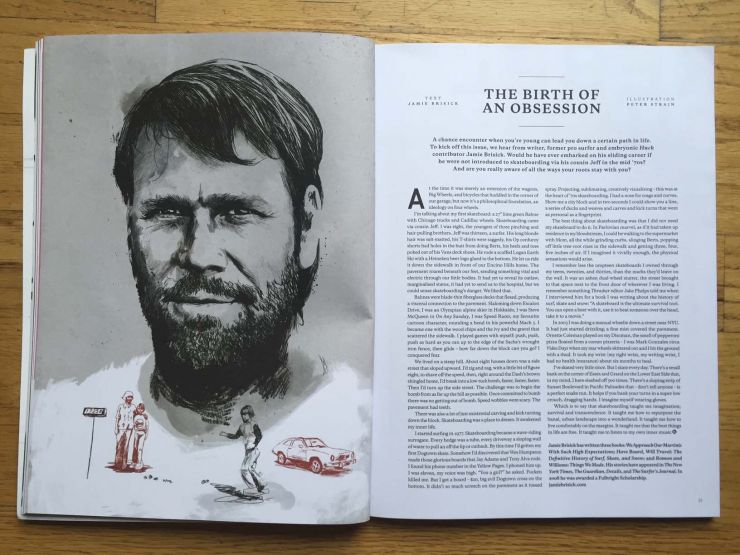

I’m talking about my first skateboard: a 27” lime green Bahne with Chicago trucks and Cadillac wheels. Skateboarding came via cousin Jeff. I was eight, the youngest of three pinching and hair-pulling brothers. Jeff was thirteen, a surfer. His long blond hair was salt-matted, his T-shirts were raggedy, his Op corduroy shorts had holes in the butt from doing Berts, his heels and toes poked out of his Vans deck shoes. He rode a scuffed Logan Earth Ski with a Heineken beer logo glued to the bottom. He let us ride it down the sidewalk in front of our Encino Hills home. The pavement roared beneath our feet, sending something vital and electric through our little bodies. It had yet to reveal its outlaw, marginalized status, it had yet to send us to the hospital, but we could sense skateboarding’s danger. We liked that.

Bahnes were blade-thin fiberglass decks that flexed, producing a visceral connection to the pavement. Slaloming down Escalon Drive, I was an Olympian alpine skier in Hokkaido, I was Steve McQueen in On Any Sunday, I was Speed Racer, my favorite cartoon character, rounding a bend in his powerful Mach 5. I became one with the wood chips and the ivy and the gravel that scattered the sidewalk. I played games with myself: push, push, push as hard as you can up to the edge of the Sachs’s wrought iron fence, then glide—how far down the block can you go? I conquered fear.

We lived on a steep hill. About eight houses down was a side street that sloped upward. I’d zig and zag, with a little bit of figure eight, to shave off the speed, then, right around the Dash’s brown shingled home, I’d break into a low-tuck bomb, faster, faster, faster. Then I’d turn up the side street. The challenge was to begin the bomb from as far up the hill as possible. Once committed to bomb there was no getting out of bomb. Speed wobbles were scary. The pavement had teeth.

There was also a lot of just existential carving and kick turning down the block. Skateboarding was a place to dream. It awakened my inner life.

I started surfing in 1977. Skateboarding became a wave-riding surrogate. Every hedge was a tube, every driveway a sloping wall of water to pull an off the lip or cutback. By this time I’d gotten my first Dogtown skate. Somehow I’d discovered that Wes Humpston made those glorious boards that Jay Adams and Tony Alva rode. I found his phone number in the Yellow Pages. I phoned him up. I was eleven, my voice was high. “You a girl?” he asked. Fucken killed me. But I got a board—$20, big evil Dogtown cross on the bottom. It didn’t so much screech on the pavement as it tossed spray. Projecting, sublimating, creatively visualizing—this was at the heart of ‘70s skateboarding. I had a nose for crags and curves. Show me a city block and in two seconds I could show you a line, a series of ducks and weaves and carves and kick turns that was as personal as a fingerprint.

The best thing about skateboarding was that I did not need my skateboard to do it. In Pavlovian marvel, as if it had taken up residence in my bloodstream, I could be walking to the supermarket with Mom, all the while grinding curbs, slinging Berts, popping off little tree-root rises in the sidewalk and getting three, four, five inches of air. If I imagined it vividly enough, the physical sensations would arise.

I remember less the umpteen skateboards I owned through my teens, twenties, and thirties than the marks they’d leave on the wall. It was an ashen dual-wheel stutter, the street brought to that space next to the front door of wherever I was living. I remember something Thrasher editor Jake Phelps told me when I interviewed him for a book I was writing about the history of surf, skate, snow. “A skateboard is the ultimate survival tool. You can open a beer with it, use it to beat someone over the head, take it to a movie.”

In 2003 I was doing a manual wheelie down a street near NYU. It had just started drizzling; a fine mist covered the pavement. Ornette Coleman played on my Discman, the smell of pepperoni pizza floated from a corner pizzeria, I was Mark Gonzales circa Video Days when my rear wheels skittered out and I hit the ground with a thud. It took my wrist (my right wrist, my writing wrist, I had no health insurance) about six months to heal.

I’ve skated very little since. But I skate everyday. There’s a small bank on the corner of Essex and Grand on the Lower East Side that, in my mind, I have slashed off 500 times. There’s a sloping strip of Sunset Boulevard in Pacific Palisades that—don’t tell anyone—is a perfect snake run. It helps if you bank your turns in a super low crouch, dragging hands. I imagine myself wearing gloves.

Which is to say that skateboarding taught me imagination, i.e., survival and transcendence. It taught me how to repurpose the banal, urban landscape into a wonderland. It taught me how to live comfortably on the margins. It taught me that the best things in life are free. It taught me to listen to my own inner music.

*from Huck issue #48