THE SURF SKATE CONNECTION

MORE FEAR AND INSECURITY THAN CAN EVER BE REPAID

In 1985 I had a ’66 powder blue Karmann Ghia, a graphite Dunlop tennis racket, a warrant out for my arrest for stealing a double scoop of chocolate fudge ice cream from Baskin Robbins, a custom-size Rip Curl fullsuit with hot pink-to-fluoro yellow tequila sunrise gussets, a tremendous amount of guilt and regret after bailing out last second on an Isla Natividad run with Surfing magazine (Karmann Ghia broke down on the 101), a tetracycline prescription (chlamydia picked up from sex in a jacuzzi — who’d have thought?), a white cat called Ninkerstinker, involuntary semi-erections that my Quiksilver ST Comps did nothing to hide –

a much-anticipated date with a Material Girl –

a decent backside snap –

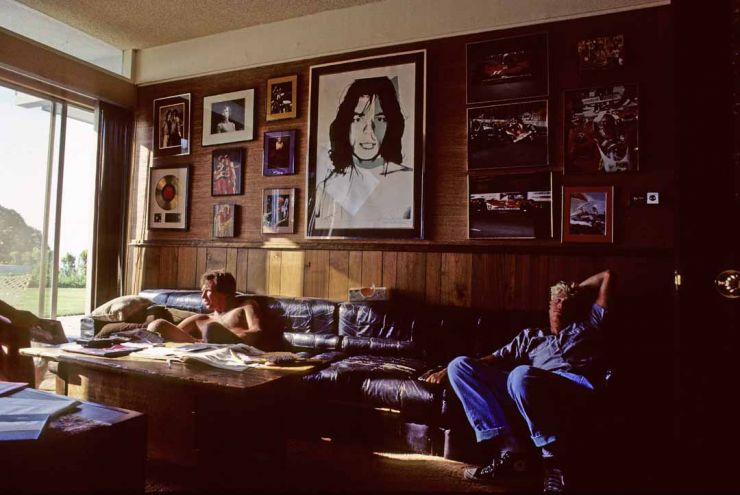

a really great pal named Rick Brown who coached and mentored me (and lived in a badass house overlooking Little Dume in Malibu) –

and not the slightest inkling that (a) technology would evolve in such a way that I’d be able to turn this shit into blogposts, and (b) I’d become so pathetic that I would actually do so.

THE LONG TWIRL: THREE DECADES OF DEREK HYND (in The Surfer’s Journal)

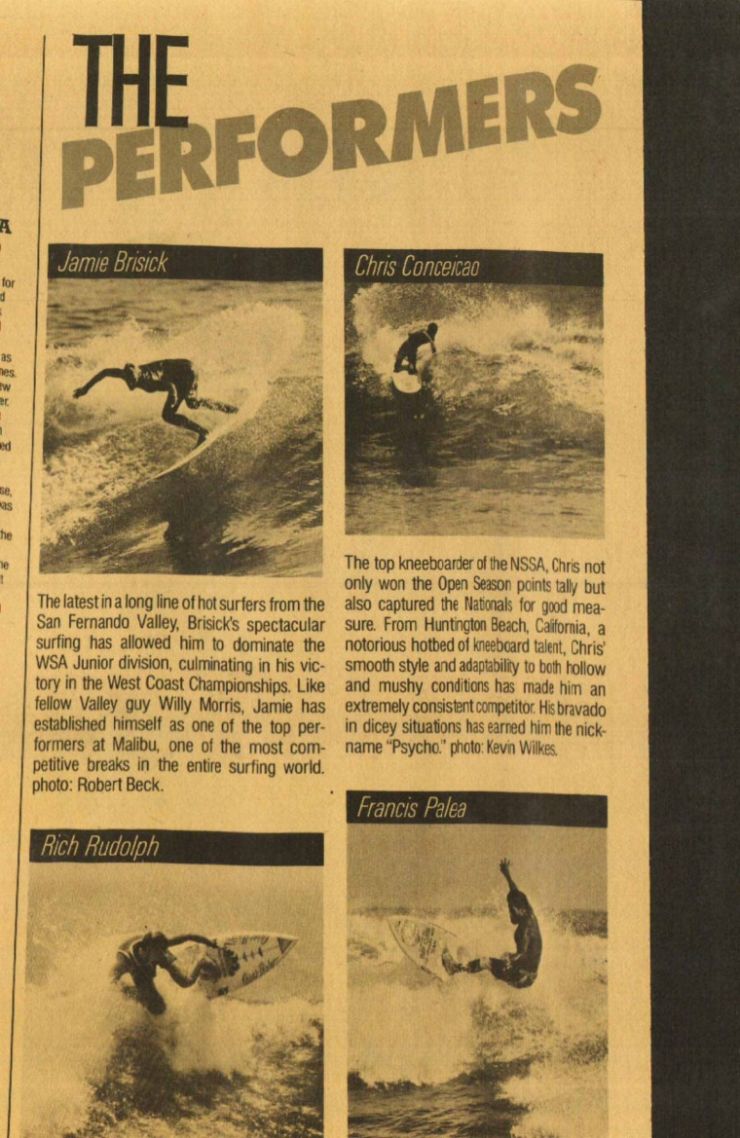

1984. I was a senior in high school, a two-time WSA West Coast Champ, and a lover of all things Australia. I was sponsored by Rip Curl and Quiksilver, listened obsessively to Midnight Oil, Men At Work, and the Sunny Boys, and very unpatriotically rooted for Cheyne, Bugs, Kong, and Chappy (as opposed to Lambresi, Barr, Buran, and Benavidez.) In confrontational moments with long finger-nailed girls who’d make my heart race, I’d revert to Aussie speak. I used words like “root,” “bushie,” “gangie,” and “kombie.” I sublimated Zuma Beach with an imagined Bondi.

My porthole into this mythical never-never land of Australian surfing was Surfing World magazine, and it was through the stories of Derek Hynd that I would learn about Occy’s violent gouges, Crammy’s screaming cutbacks, and Barton Lynch’s surgical lip pierces. I read about mythical outer reefs in WA, hitchhiking trips between NSW and “the Goldy,” and outlandish, perverse acts at Newport Plus Boardriders Club victory parties. I can still see his clever byline: a cycloptic eye with the words “Hyndsight” beneath it, a multi-layered pun that flew over my head at the time.

I first met him in ’86 when I joined the ASP tour. He was coaching Occy, Gary Green, Wayne Jaggard, Mitch Thorson and a handful of other Billabong-sponsored riders at the time, as well as writing his much-anticipated Top 30 assessments with trademark conviction. He was anti-drug, but had a bent for getting drunk and dancing spasmodically to old punk, namely Joy Division and The Clash. Through Derek’s unforgettable dispatches I would learn the meaning of words like “journeyman” and “bastard desire,” and come to understand that in the game of professional surfing, an unsettled beef with a cruel stepfather or a nasty rivalry with a tourmate can be fuel, i.e., nice, wholesome guys rarely finish first.

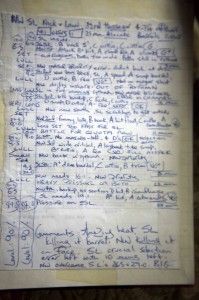

In ’88 Rip Curl hired him to coach the team, of which I was a member. I was as excited about a glimpse into his inner workings as I was improving my lackluster results. He kept obsessive, blow-by-blow contest diaries, which he wrote in tiny print. He recorded rides with the visceral animation of an avid finger boarder. A Tom Curren ride would look as follows: TC: 4 ft. left, vert, vert, big vert, float, cutback, snap, closeout float. A rail bog or mistimed turned was simply an “error.” He didn’t score waves with numbers but rather P (poor), A (average), G (good), and VG (very good), with added plus- and minus-signs like they do on school report cards. Occys, Currens, and Potters occasionally scored XLs.

Our one-to-ones at water’s edge before heats were unforgettable, and recall Slugworth in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory seconds after each kid found his golden ticket.

“If you’re not on a wave within the first five minutes, it’s over, James,” he’d whisper with a hand-cupped mouth so my jersey-clad opponent couldn’t hear.

“You’re surfing against Gerr, who’s faster, more powerful, and more flamboyant than you. So your only hope is to get the lead in the first ten minutes then sit on him.” (This was when the priority buoy was in full effect, and starving your opponent for waves was an oft-exploited tactic.)

“Don’t even think about the lefts. It’s rights or nothing. And it’s maximum hits per wave. Bottom turn, crack. Bottom turn, crack.”

He coached Curren, Damien Hardman, Marty Thomas, Wes Laine, Stuart Bedford Brown, John Shimooka, and several others, which was quite genius when I think of it now. By taking blow-by-blow notes of nearly every heat from the early rounds onward, he was perhaps more in tune with the judges than even they themselves were. By the time he got to the crucial Curren or Hardman heats, he knew exactly how they were scoring tubes, length of ride, the lateral vs. the vertical, rights vs. lefts, etc. This is not to mention the fact that he was getting paid on a sliding-scale incentive. Curren needed to get, say, an 5th or above for Derek to be paid, whereas someone like myself needed a 17th or better. If my numbers were correct, he was making a small killing.

He spoke with a slow, measured drawl, and thrived on making controversial, totally-out-there calls. He rarely brushed his hair. He had horrible posture and often slumped in a top-heavy, writer’s stoop, which was kind of revolutionary set against the puffed up, pigeon-chested pros. Often he’d shake his pen at me, which I like to think sprinkled a kind of fairy dust that would later lead me to writing.

And then at the IMB Margaret River Pro he suddenly decided to enter the contest. It came out of the blue. I knew that he still ripped, but he generally did so in the shadows.

In a memorable Surfing World piece he called Occy a “potential fool or potential superstar,” and in a strange sort of manifest, Derek’s lines across Margaret’s machinelike, howling offshore left with spiraling inside section was a potential gimmick or potential contest winner. Where the rest of us hunted the lip, Derek raced for the shoulder, carved low-center-of-gravity roundhouse cutbacks, then, at the apex of the figure eight, did this dramatic, head-tweaking layback on the rebound. It was freakish, poetic, the signature move of a single-eyed eccentric man, and I remember thinking that he might win the contest.

In the final round of trials we found ourselves in the same heat. By this time we’d become good friends. We talked books, music, family, and caramel-skinned, non-English-speaking women. We shared hotel rooms and rent-a-cars. I started out the heat horribly while he found a solid rhythm. We were side by side when suddenly a ten-foot, shimmering teal blue wall headed straight for the two of us. I was on the inside. We both paddled out to meet it. In the heat of hyperfocus and jockeying, Derek blurted out, “Gimme this wave, James, and I’ll buy you fifteen beers.” It was the detail that threw me off. Rather than think, “Fuck you, Derek” and defend my position, I pondered the “fifteen beers” part, the notion of being quotable in frenetic moments, while he of course slithered to my inside. I lost; he went a few rounds further then got KO’d.

Our friendship expanded and I learned. Often we’d be in some cheap hotel room in Hossegor or Ericeira and I’d be doing my stretches while he’d be sprawled stomach-down on the carpet, scribbling out in a single draft whatever profile or contest report for Surfer. It was fascinating to see our traveling circus translated to the page. What was vague and uncertain to me was indisputable to Derek. Nick Wood was not a slightly reclusive guy with a vampish girlfriend who liked to drink, but rather he was “The Phantom” and she was “The Black Widow.”

I was thoroughly impressed when he showed up at the Rip Curl Pro with windswept hair and tales of Transylvania. A Dracula fan, he always wanted to see the place. He’d gone solo, then driven straight through the night to Hossegor. I knew very few people who did this sort of thing.

On a sunny day at the Gunston 500 in Durban he introduced me to a curvaceous, late-twenties blonde. “James, meet my wife.” I didn’t even know he had a girlfriend. His eccentric J-Bay house came soon after, as did his spectacular glass-and-wood palace in Chile.

When I fell in love with a caramel-skinned Sydney girl and relocated to Derek’s hometown of Newport Beach, he was right there, whispering twisted, beautiful, coach-like advice. And when we fell apart two years later he was right there again, picking me up in his powder blue beater Mercedes, taking me to parties, feeding me Cooper’s and reassurance.

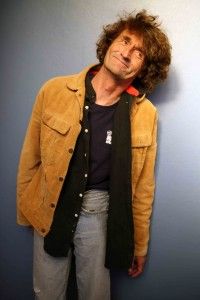

If I sound overly gushing I apologize. I’m fresh back from Sydney for the first time in fifteen years. I found Derek at Jack McCoy’s office, located in a non-descript red brick apartment block in South Avalon. His unshaven face was covered in salt and his hair was Albert Einstein-like, but brown not gray. He wore Blundstone boots, faded jeans slung high, and a ragged, logoless t-shirt. He was typically unenthusiastic in his greeting. He did not smile considerately, but when something was funny, he laughed passionately, and when telling a story he painted it with his hands. He’s fifty-two. He wakes up and checks the waves first thing. He recently moved back into the house he grew up in to support his widowed mother. He’s a single, doting, hands-on father.

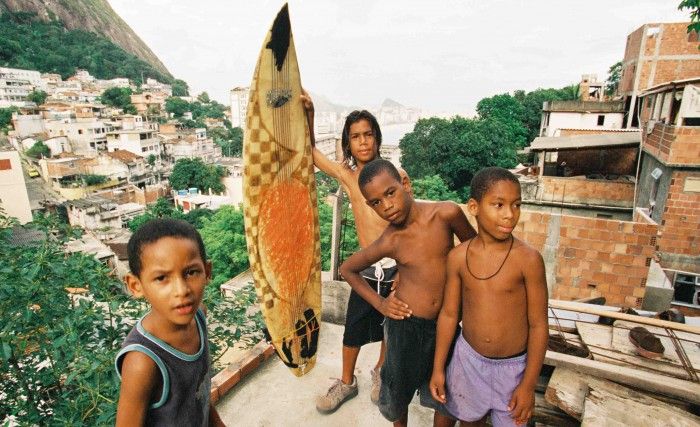

Most importantly, he does 360s. Lots of ‘em. On finless boards to which he adds ¼” inch fiberglass ridges, he stays extremely low, often grabbing rails, and is essentially at the mercy of the wave. He planes along at dragless hyperspeed, and twirls randomly and frequently, doing more 360s on a single wave than your average surfer does in a lifetime. But more important is the spirit of this weirdness. It looks ridiculously fun. It also looks like something you’d find smiling, Jockey-short clad twelve-year-olds doing on the nose-half of a broken board in deep Mexico.

The boundaries of the mid-life surfer are constantly being stretched. The usual path is big waves, elegant noseriding, or masterful lines. But we’ve never seen anything like this before.