1985. Ronald Reagan. “We Are the World.” AIDS. “Like a Virgin.” An exploding surf industry. A powder keg of a world champion: Tom Carroll, uber-athlete, hard charger—at giant Pipeline and at the nightclub at 1:44 a.m. I had feelings that scared me for a girl named Julie. And something dirty with Carolyn. Mostly I had a 6’2” Al Merrick thruster and three WSA West Coast Championship titles.

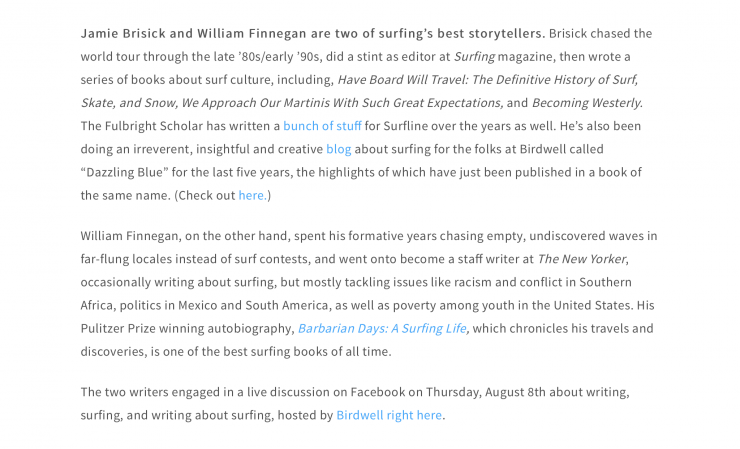

I turned pro that summer. To kick off my giant leap, Quiksilver, my sponsor, sent me on a photo trip to Natividad. Photo trips were a new thing. There’d always been surf trips (Endless Summer, Naughton-Peterson), but photo trips were more about getting ad shots for the brands than editorial for the mags. Also new was the “photo guy” (or “photo whore,” depending on who you were talking to). Today we call them “freesurfers” without blinking an eye. But back then the notion that you could earn a living simply by getting your mug in the mag was unprecedented.

Leading this charge was my friend and mentor, Willy Morris. His 6’2”, 220-pound frame did him no favors in the ASP events, held way too often in small waves, but he could chuck giant spray that looked great in photographs.

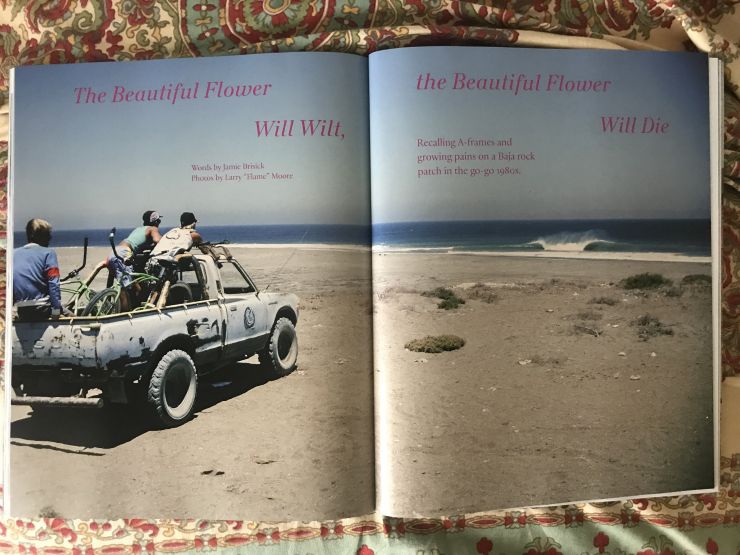

It was Willy who put together our trip. He and Surfing magazine photo editor Larry “Flame” Moore had been monitoring the chubasco swell; the buoys were 4 to 6 feet at 20 seconds—perfect for Natividad. Willy picked me up in front of my house at 4:30 a.m. In his new, gunmetal-gray Jetta, bought with the money he’d been making through photo incentives, we headed south to the border and followed the much-potholed 1D coastal road to Ensenada Airport. There we met up with the rest of the crew: Richard Cram, Bryce Ellis, Sam and Matt George, JP Patterson, and Flame.

The morning sun blazed. The wind whipped precariously, especially given the flimsy look of the propeller plane that would fly us the 450 kilometers south to Isla Natividad, a tiny island home to Open Doors, a beachbreak that served up whomping A-frames. It was hailed as a sort of photo studio: Prevailing winds blew offshore, and it was brilliantly front-lit by the afternoon sun.

The seating arrangement on the plane was more bus than aircraft. A handful of leathery fishermen occupied the first couple rows. They laughed a lot, mostly at us gringos. An elderly woman sat behind them. She wore what looked like a nun’s tunic, and on her lap she held a live chicken. Behind her was a wiry old man holding a leash attached to a scruffy gray goat. Our surfboards occupied the center aisle—a major fire hazard, but there was no one to regulate that stuff.

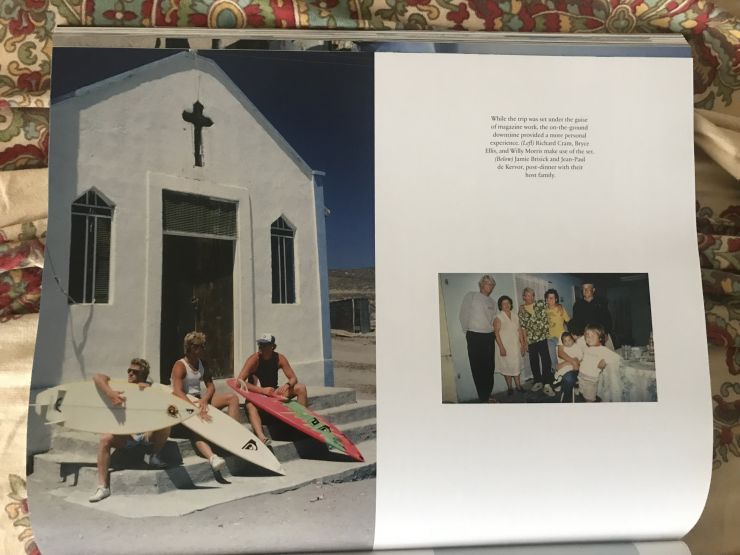

I did not know my fellow photo-trippers when we boarded the flight, but by the time we hit the ground at Natividad I felt like I did. Flame was meticulous, hyper-organized, possibly a germophobe. He also guarded his camera gear as if someone might steal it. Clad in Reeboks and sweatpants, Bryce and Crammy were serious athletes. They hid behind Walkmans, did the occasional forward bend, and seemed slightly put off by the Tres Mundo of it all. JP Patterson was bodyboarding’s first legit pro, and spoke of Waimea barrels. Sam and Matt exuded the “When in Rome…” spirit. They did not speak Spanish, but nonetheless joked with the fishermen, charmed the old lady, petted the chicken, scratched the chin of the goat, and poked their Heckle-and-Jeckle heads into the cockpit to chat up the pilot.

Approaching Natividad’s dirt landing strip, heads pressed to the windows, we saw what from above looked like excellent waves. They were exactly the pounding peaks I’d seen in recent issues of Surfing. The wind blew a strong offshore—or was that the wind kicked up from our plane? We flew so low over the surf that it was hard to tell. Our landing was immaculately smooth. The goat did not bleat. The chicken clucked only a little. We exited and dragged our gear up the landing strip and across a scrubby field to a group of cinder-block bungalows that reminded me of Fred and Wilma’s house in The Flintstones.

Natividad was occupied by a couple dozen families, most all of them fishermen. There were no hotels. You rented bungalows, which were really just family houses. We checked in with the family Flame had stayed with on his last trip, and walked across the center square to our accommodations. I bunked with Willy and Flame, the Aussies took the bungalow across from us, and Sam and Matt took one around the back. Our room had three cots, a couple of plastic chairs, a TV, and lots of Virgin of Guadalupe artifacts on the walls. We did not bother to unpack. We grabbed our boards and wetsuits and bolted for the surf.

The waves were throaty, the water surprisingly chilly. Flame set up his tripod down the beach from us and shot into the rights. I got a few, though my timing felt off and I was nervous about the camera. The others surfed brilliantly. Willy in particular rode with masterful command, picking all the right waves and hitting all the right spots.

We surfed until the sun disappeared behind the horizon and the sky turned to tequila sunrise, or more like tequila sunset. On the walk back we passed a gaggle of barefoot kids playing soccer on the landing strip, their shoes set up as goal posts. They laughed at us, just as the fishermen on the plane had. Matt George dropped his board and joined them for a few kicks.

At our bungalows we showered under a trickle of cold water that dripped from 6 inches of hose poking out of a cement wall. Then we dressed and headed over to the main house for dinner, which Flame explained worked like a B&B, albeit with all three meals. Our hosts—Familia Gutierrez, I’d learn—served up rice, beans, a baked white fish, and a lobster soup. We drank one beer each. We talked about Hawaii. Sam and Matt described a recent luau they’d attended. “Hawaiians don’t eat till they’re full, they eat till they’re tired,” said Sam. Flame told a terrible story about a guy who’d face-planted into the shallow sandbar at Open Doors and broken his neck. There were no medical facilities on Natividad, and, by the time they had airlifted him out of there, he’d downed a full bottle of tequila to kill the pain.

We finished our meals, thanked the Gutierrezes, and ambled back to our rooms. Willy and Flame talked about boats—the Radon Sport 21, Hobie Cats. Sam and Matt spoke passionately about a recent marathon they’d run, and, as we passed my bungalow, I understood it that I should follow them, and we said good night to the others.

“Set your alarms for six o’clock,” were Flame’s final words.

In their room, furnished much like ours, Sam laid on the concrete floor with his legs pressed vertically up the wall. “Good for circulation,” he said. Matt raved about a girl he’d met on a recent trip to Tahiti.

“It was like we’d known each other for 11 lifetimes, and Jame, we fell in love. It was the real stuff. I’d hurl myself in front of a train for this girl.”

“Where is she now?” I asked.

“In her little cottage up in the trees above Taapuna, probably cooking dinner for her father or shampooing her little brother’s hair. She had these breasts that looked like they carried milk for the entire world. She was a flower. A beautiful flower.”

“Why didn’t you bring her home with you?”

“Ah, no! No, Jame. It’s not like that. No. I’ve traveled enough to understand these things,” he said, and brought his hand to his heart as if pledging allegiance. “You can admire the beautiful flower. You can smell the beautiful flower.” He shut his eyes and inhaled sensually. “You can even touch the beautiful flower.” He swirled his fingers in a little circle. “But you cannot pick the beautiful flower and bring it back to smoggy, stressed-out Southern California, because it will wilt and it will die. Sam, back me up on this one. Am I right?”

Sam still had his legs up the wall: “You’re not always right, Matt, but you’re never wrong.”

Matt moved over to the TV and flipped through the stack of videotapes atop it.

“Oh, yeah! Sam, Jame, we have Deep Throat.”

He held up the sleeve and read aloud: “How far does a girl have to go to untangle her tingle? Eastmancolor. Adults only.”

Matt inserted the tape into the VCR, and in that little room alongside the landing strip on Isla Natividad, population about 75, we watched Deep Throat from start to finish. And for those 61 minutes, Sam and Matt George, the most talkative men I’d ever met in my life, did not speak a single word.

I couldn’t sleep that night. Too much stimulus: Linda Lovelace. Too many vivid impressions: Crammy’s backside cutback. Too much snoring: Flame. Tossing and turning—mattress coils like teeth, pillow like a stone slate—I thought about girls.

A few nights before I left for Natividad, I was headed out the door to go to a party when my father, seated alone at the dinner table, stopped me.

“You know,” he said, “when you’re with a girl, Jamie, it’s just you. It’s not Jamie the pro surfer or Jamie the guy in the surf magazine. It’s just Jamie. It’s just you standing naked, no masks, no labels. Know what I mean?”

I thought about Julie and wondered if my inability to talk to her was some kind of survival mechanism. If we’d have fallen in love, then what? Instead of falling in love with Julie, I slid into something emotionless with Carolyn, a model and occasional purse-snatcher. (I’d witnessed the latter firsthand.) I met her on a Quiksilver shoot. She was on parole for her second DUI. She was 17. Carolyn had thick brown hair and porcelain skin and pouty lips that more often than not were clamped around a Marlboro Red. Her giraffe-ishly long legs poked out of ridiculously high skirts. She called her girlfriends “hooker,” and eventually started calling me “hooker.”

Carolyn lived in a one-bedroom apartment in Encino that her absentee father paid for. She liked to have sex on the shag carpet, where we’d worm our way closer and closer to the fireplace, so that burning-hot faces and climax were synchronized. I spent about a half-dozen nights with her. And on every one of them—usually late, close to midnight—there came a knock on the door. Carolyn would raise a finger to her lips. The knocks would advance to pounds. The doorbell would go haywire. Then it would stop for an hour or two. Then it would start again. I noticed a difference in the cadence and force of the first and second round of knocks, and wondered if there was more than one man trying to get at her.

The next two days on Natividad were terrific. The swell came up a touch; the wind continued to blow offshore. The A-frame-shaped waves sometimes connected with a second A-frame, so that we’d drop down the face in a low tuck with rear arm jammed into the water to create drag to slow you down and maximize tube time, then exit the tube, pump, pump, pump, and backdoor the next A-frame, which was like an abbreviated, watery version of that tunnel we drove through on Malibu Canyon.

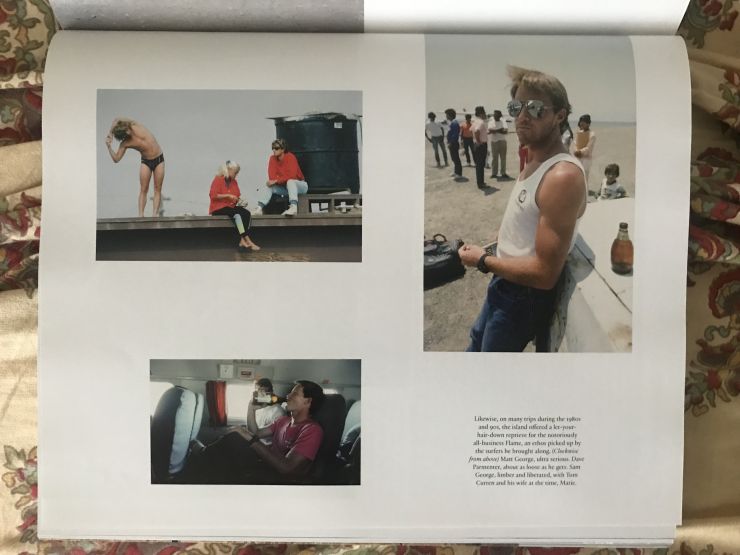

Willy carved huge, winged top turns. Crammy and Bryce sliced and diced. Sam and Matt seemed to take more pleasure in the recounting of the rides than the rides themselves. At dinner they were like a pair of seasoned sports announcers doing their post-game parsing. Flame spent most of the hot and bright hours standing behind his 600mm lens, though he did swim out and shoot from the water a couple of times. Open Doors broke hard in shallow water. He less swam than stood in the waist-deep impact zone and hollered us into waves. It didn’t matter if they were makeable or not. It was closer to modeling than proper surfing. We’d stroke, pop to feet, pose in barrel, then get crushed. In one rag-dolling wipeout, I felt Flame’s fins, head, and housing. It was strangely intimate. When we surfaced four seconds later, I felt like I knew him better.

These were pre-digital days, of course, so there were no photos to look at after, only Flame’s recollections. “That thing was a frothy pit,” he said of one of Willy’s waves over lunch. Hoping to get a laugh, I turned to Sam and Matt and said, “Natividad is full of frothy pits.” Matt rested a paternal hand on my shoulder and said, “Ah, Jame, that’s just the porn talking.” And for the rest of the trip that became our inside joke. And to this day, 35 years later, I’ll run into Sam and Matt and they’ll wait for the right moment and give a slight shake of the head and say, “That’s just the porn talking.”

The last day of the trip was September 17, my 19th birthday. I told Willy that morning. He told the rest of the crew. At breakfast I was casually wished a happy birthday. By dinnertime we were all celebratory. Sam wore a sombrero he’d bought in Ensenada. Matt wore a Lawrence of Arabia scarf. We ate grilled snapper with a citrus sauce and rice and beans. There was more beer than the previous nights. And as Mamacita cleared the plates from the table, Willy produced a bottle of tequila. He poured out shots. We toasted. Mamacita and Papacito appeared from the kitchen with a chocolate birthday cake topped with 19 lit candles. All sang “Happy Birthday,” the Spanish and English running over the top of each other. I closed my eyes, made a wish, and blew. The cake tasted dusty, in the same way that all of Natividad did. It was good and not too sweet, the frosting thick and gooey.

The fun didn’t stop there. With the tequila bottle in hand, Matt led us outside and around the back of the bungalows to a small courtyard where nearly every resident of Isla Natividad had gathered. They were waiting for us. The gringo’s birthday was cause for celebration. Cans of beer topped the sole picnic table. An elderly man in a cowboy hat played a guitar and blew into a harmonica. Kids lit firecrackers and threw them into the night. Hanging from a tree was a piñata, or a pillowcase doubling for one. After the first bottle of tequila was finished, a second one came out. There were no glasses. We swigged from the bottle and passed it along.

Once we were good and wobbly, Matt came over, kissed me on the cheek, unfurled his scarf, and wrapped it around my eyes. A blindfold. I heard Spanish-speaking voices moving closer. Someone handed me a baseball bat. I heard kids’ laughter. I smelled cigarettes. Little hands grabbed my hands and led me around in one circle, two circles, three circles, four. The laughter rose. I stumbled, nearly fell over. “Àndale!” they yelled. I stepped forward in what I thought was the direction of the piñata and swung. I hit nothing. Laughter. I stepped to the left and tried again. Nothing. I swung furiously and widely, hoots, hollers, “Àndale!”s. Then I connected. I heard the sound of the piñata’s guts spilling on the ground. I peeled off the scarf. On hands and knees the village kids picked through the contents. It was not candy, but surf stuff—leashes, bars of wax, at least a half-dozen Astrodeck tail patches, a few Nose Guards, and a bunch of stickers.