The first setback in our pre-teen lives was when we moved from Encino to Westlake Village. Not only did it separate us from our beloved cousins in West LA, but it plopped us in the center of a newly developed suburban community that, even at eleven, ten, and nine years, struck my brothers and me as contrived and superficial. We’d tasted enough of the city to know about big boulevards where all walks of life intersect, and suddenly we were expected to make due with cul de sacs and white-bread neighbors.

There was also the issue of the Valley. Skateboarding had taught us that all zip codes on the inland side of the Santa Monica Mountains were uncool. Our Encino house had been up in the hills—neither beach nor val. Westlake was indisputable. As cousins Pete and Jeff liked to say, “You’re not just Val, you’re Deep Val.” Vals looked like their moms dressed them. Vals asked too many questions, rode with erect, dorky styles. Beach kids exuded a go-with-the-flow grace. They skated with low centers of gravity, dragged their hands on the pavement. Later, when skateboarding took to the air, the distinction became even more pronounced. Vals reached between their knees to grab the rails of their boards, forming cowboyish bandy-legs. Beach kids grabbed from the outside of their rear leg, forming knock-knees, which was pure surf style. When we skated localized spots on the Westside, Jeff made us promise never to mention Westlake. “If they ask, tell ‘em you live on Ocean Park and 15th, and go to John Adams.”

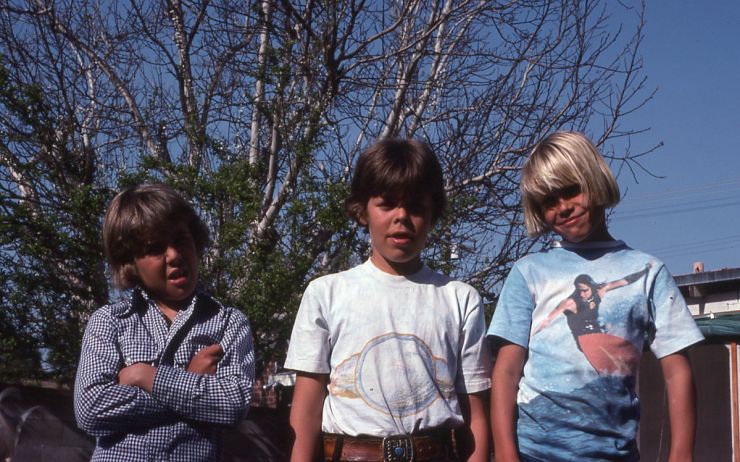

Mom and Dad only wanted the best for us: a bigger house, better school district, and parks and playgrounds for toddler Jenny. But Kevin, Steven, and I resisted. We shunned our new classmates and stuck close together.

There was one saving grace, though, and that was the freshly paved streets, sidewalks, and driveways that turned Westlake into a skateboarding wonderland. Where others saw affordable four-bedroom homes in models A, B or C on quiet, oak-studded streets, we saw a bolt down the green belt, a tight turn onto the slanted sidewalk, a low crouch under a row of prickly ferns, a slashing kick turn at the top of the Halls’s driveway, a slalom course of stray wood chips, a dip then rise where, with enough speed, you could get an inch or two of air, and as crescendo, at the top of our driveway, a screeching, sprawling Bert.

Berts were to skateboarding what peeling out was to driving muscle cars. Named after surfer Larry Bertlemann, they made a loud farting sound. In a crouch, you planted your front hand and skidded the board around in a sharp 180-degree arc. They felt defiant and sexy. They also ripped holes in our pants, showing off the fact that we wore boxers not “butt huggers,” which, in elementary school, was a kind of political statement.

I was obsessed with the “Dogtowners,” a band of raffish, pot smoking, wildly gifted skaters from Santa Monica and Venice. I studied their pictures in Skateboarder, noting not only their knock-knees and splayed fingers, but also their facial expressions. Tony Alva pursed his lips. Stacy Peralta edged his tongue out of his mouth. When Mom offered to buy us back-to-school clothes, I flipped through the Dogtown articles and made a list: oversized Pendleton with red checks, Mr. Zog’s Sex Wax T-shirt, low slung Levi’s cords, tube socks bunched at the ankles, two-tone Vans deck shoes. After shopping at the Oaks mall, I took my new gear out to the backyard and grinded it against the pavement to make it look more “Dogtownerish.” I drew Dogtown crosses on my notebooks and my desk at school. I drew imaginary Dogtown crosses on my thigh with my index finger. I read about the elfin “Jay-Boy” Adams’s death-defying trick in which he skates at full speed up to the moving Pacific Ocean Park bus, skids into an extended Bert that literally throws his lithe, horizontal body under the bus, then snaps his board around seconds before the rear wheels crush him.

There were no busses in Westlake but there was a foldout table in our garage. We set it up at the top of the driveway. With extension cords, we placed our record player on top and blasted Johnny Winter. Weaving through the “Sorrelwood Run” as if it were a bustling street in Santa Monica, we aimed for the music. Inches before colliding with the table we tucked, planted hands, and pulled sprawling, melodramatic Berts—boards and bodies under table just like “Jay Boy.”