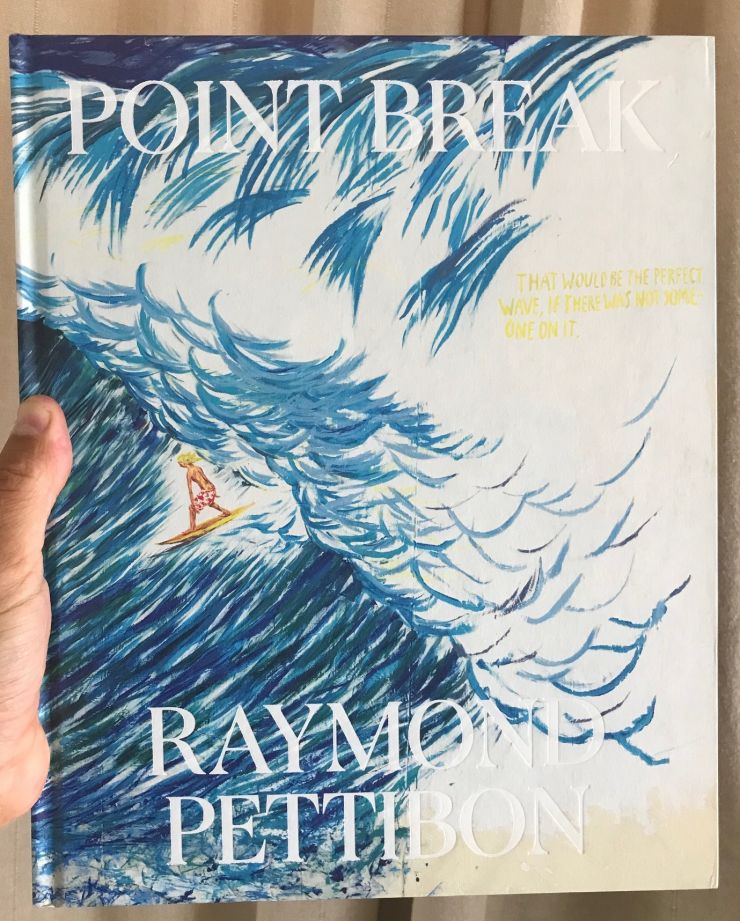

Riding Giants with Raymond Pettibon

Jamie Brisick

Raymond the Fabulist

Raymond likes the big stuff. Though the waves of his early surfing days at Hermosa BeachPier, in California, were mostly small and gentle, he found his lust for heavy water on a family trip to Hawaii in 1974. On a gray and windswept afternoon at fabled Sunset Beach on the North Shore of Oahu, seventeen-year-old Raymond paddled out into eight- to ten-foot surf, fell into a preternatural groove, and repeatedly connected waves from the west peak all the way through to the inside bowl. He’s been chasing swells up and down the coast of California ever since.

“Surfing big waves at Deadman’s, in San Francisco, taught me how to wear the wrath of the Pacific Ocean on my head and to just enjoy the pummelings,” he told me. “Mavericks is like ten football fields of freezing-ass steel-gray cruelty, with rocks and sharks—that was a lot of fun, until the media turned it into a circus. Now I’m happiest farther north. I’ll put my head down for months at a time to finish work for a show. But as soon as it’s done, I’m all loaded up with the boards and the dogs. There are spots in northern Oregon where it’s just you and God.”

I asked why he hasn’t been more forthcoming about his surf jones with the art world.

“Crowds,” he said. “The more you talk about breaks, the more the hurried masses will flock there. I had a bad dream the other night. I was out surfing one of my secret spots, and I look over and there’s Peter Doig and Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons out on longboards. Between waves they wanted to talk shop. I don’t talk shop when I’m in the water.”

Actually, none of this is true. In the two decades that I have known Raymond, I’ve never known him to surf. But he has produced boatloads of surf-themed work since the eighties. And among his many alter egos, one is a big-wave surfer.

At an art dinner in New York a few years ago, I sat across the table from Raymond, who sat next to the boyfriend of a fashionista. Over plates of pizza and pasta and many glasses of Nero d’Avola, I watched Raymond and the boyfriend engage in what looked like deep conversation. After dinner a group of us stepped out to the sidewalk. Someone suggested we go for a nightcap at a bar around the corner. All were in except for Raymond and his girlfriend, who said they were tired and needed to get home. Walking to the bar, I fell into step with the boyfriend.

“That guy I sat next to, what’s his name, Ray—wow, so interesting!” he said.

“How so?” I asked.

“He’s a dog breeder. He breeds pit bulls that fight to the death in these highly illegal dogfights. There’s this whole underground culture. Apparently, he’s one of the top breeders.”

I silently chuckled. A few years earlier, I was writing a profile of Raymond, and in my efforts to better understand him, I spoke with the artist Gomez Bueno. Gomez fondly recalled a period in the early nineties when he and Raymond would go to openings, concerts, horse races, and Dodgers games together. Gomez would pull up in front of Raymond’s studio in Long Beach and toot his horn. Raymond would come out and hop in the car. Gomez would ask how he was doing, and Raymond might say, “Much better now that Paris and I broke up,” and so would begin an hourlong conversation through Los Angeles traffic about Raymond’s fucked-up relationship with Paris Hilton. Or it might be, “Been getting my moonsaults down,” and he’d launch into details of his training regimen as a pro wrestler. Or it might be about fighting in Vietnam, albeit from the Vietcong side.

“It was always very creative and colorful,” said Gomez. “And I was just totally blown away by his wealth of knowledge, how he could just keep pulling up details. It was like witnessing someone creating a work of art, just with his talking. And he would never end it with, ‘I’m just kidding.’ If you were stupid enough to believe it, that was your problem.”

I’m reminded of a quote by Oscar Wilde: “Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.”

Raymond the Omnipresent

I first encountered Raymond’s work in the early eighties. His album covers for Black Flag sat across the bedroom from my five-foot-six McCoy single fin. His flyers were pasted at punk venues like the Whisky, Stardust Ballroom, Olympic Auditorium, and Madame Wong’s. His Black Flag logo could be seen on many a sweaty, stage-diving kid’s T-shirt. At that time, outwardly, punk and surfing appeared as almost opposites, but in fact they shared much in common. Both were on the margins; both bucked the status quo.

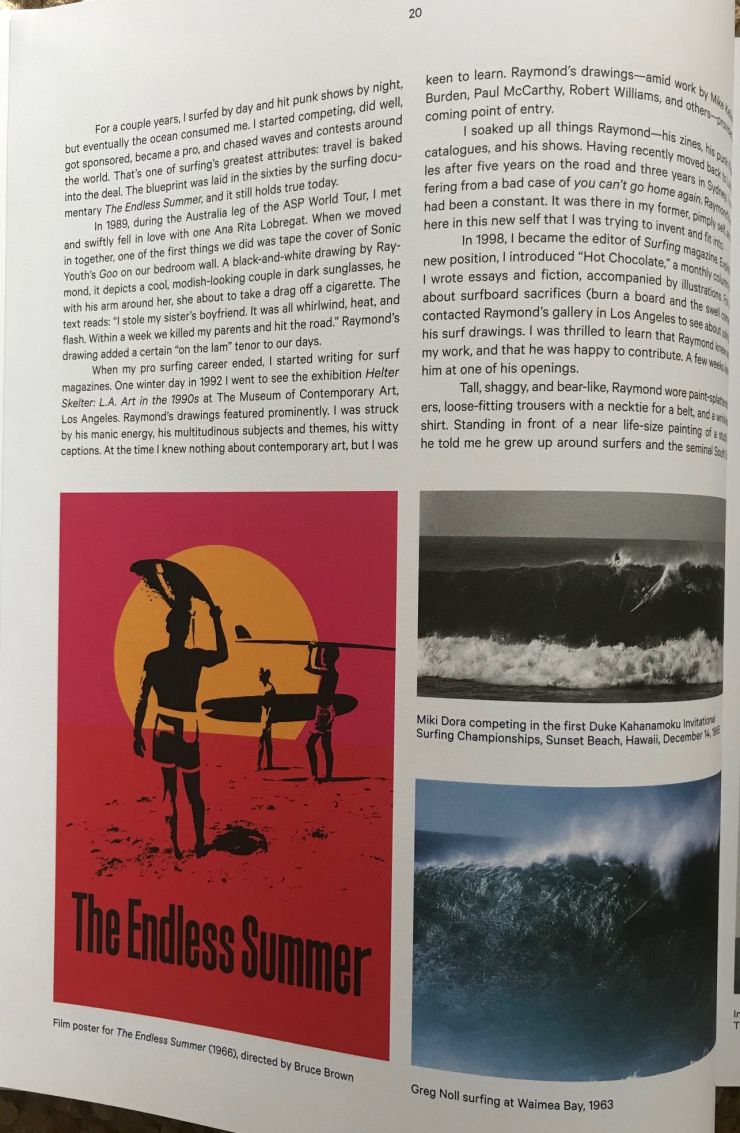

For a couple years, I surfed by day and hit punk shows by night, but eventually the ocean consumed me. I started competing, did well, got sponsored, became a pro, and chased waves and contests around the world. That’s one of surfing’s greatest attributes: travel is baked into the deal. The blueprint was laid in the sixties by the surfing documentary The Endless Summer, and it still holds true today.

In 1989, during the Australia leg of the ASP World Tour, I met and swiftly fell in love with one Ana Rita Lobregat. When we moved in together, one of the first things we did was tape the cover of Sonic Youth’s Goo on our bedroom wall. A black-and-white drawing by Raymond, it depicts a cool, modish-looking couple in dark sunglasses, he with his arm around her, she about to take a drag off a cigarette. The text reads: “I stole my sister’s boyfriend. It was all whirlwind, heat, and flash. Within a week we killed my parents and hit the road.” Raymond’s drawing added a certain “on the lam” tenor to our days.

When my pro surfing career ended, I started writing for surf magazines. One winter day in 1992 I went to see the exhibition Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Raymond’s drawings featured prominently. I was struck by his manic energy, his multitudinous subjects and themes, his witty captions. At the time I knew nothing about contemporary art, but I was keen to learn. Raymond’s drawings—amid work by Mike Kelley, Chris Burden, Paul McCarthy, Robert Williams, and others—provided a welcoming point of entry.

I soaked up all things Raymond—his zines, his punk flyers, his catalogues, and his shows. Having recently moved back to Los Angeles after five years on the road and three years in Sydney, I was suffering from a bad case of you can’t go home again. Raymond’s artwork had been a constant. It was there in my former, pimply self, and it was here in this new self that I was trying to invent and fit into.

In 1998, I became the editor of Surfing magazine. Exploiting my new position, I introduced “Hot Chocolate,” a monthly column in which I wrote essays and fiction, accompanied by illustrations. For a piece about surfboard sacrifices (burn a board and the swell comes up), I contacted Raymond’s gallery in Los Angeles to see about using one of his surf drawings. I was thrilled to learn that Raymond knew and liked my work, and that he was happy to contribute. A few weeks later, I met him at one of his openings.

Tall, shaggy, and bear-like, Raymond wore paint-splattered sneakers, loose-fitting trousers with a necktie for a belt, and a wrinkled dress shirt. Standing in front of a near life-size painting of a studly horse, he told me he grew up around surfers and the seminal South Bay surf shops—Jacobs, Weber, Bing, Rick. We talked about how California surfing was once escapist, quasi-transcendentalist, and how that all changed in the sixties with the arrival of Gidget, the beach party films, and surf music.

“I’m interested in those early, pre-surf craze days,” he said. “I like the purity, the ‘man alone at sea.’”

Raymond knew his surf films and also the surf photos from magazines. eHeHHe knew the mythos, the way commercial interests had sullied the purity. He knew about the icons: Miki Dora, aka “Da Cat,” the Malibu rebel who went on a global surf odyssey funded with forged checks and stolen credit cards; Greg Noll, aka “Da Bull,” the big-wave pioneer who, on December 4, 1969, rode a wave so massive and death-defying that it would be his last.

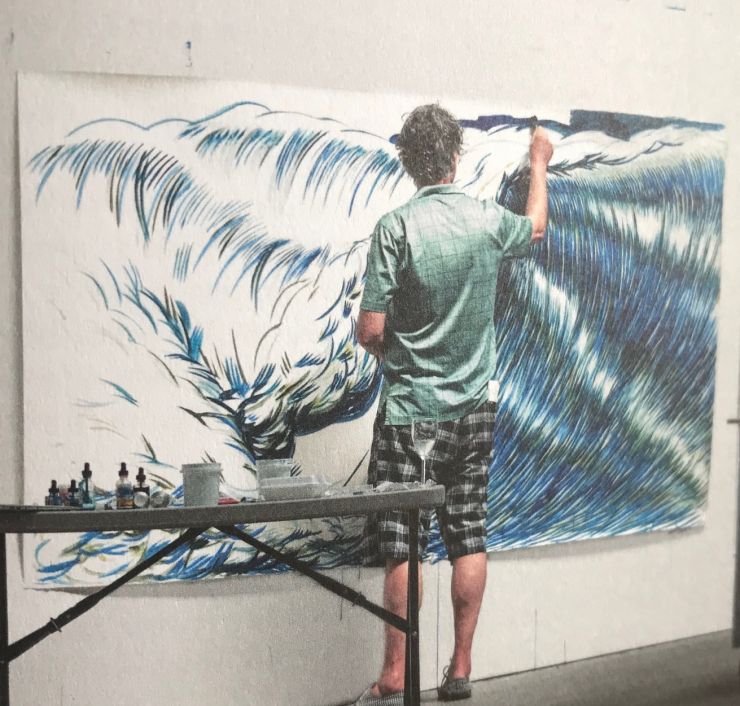

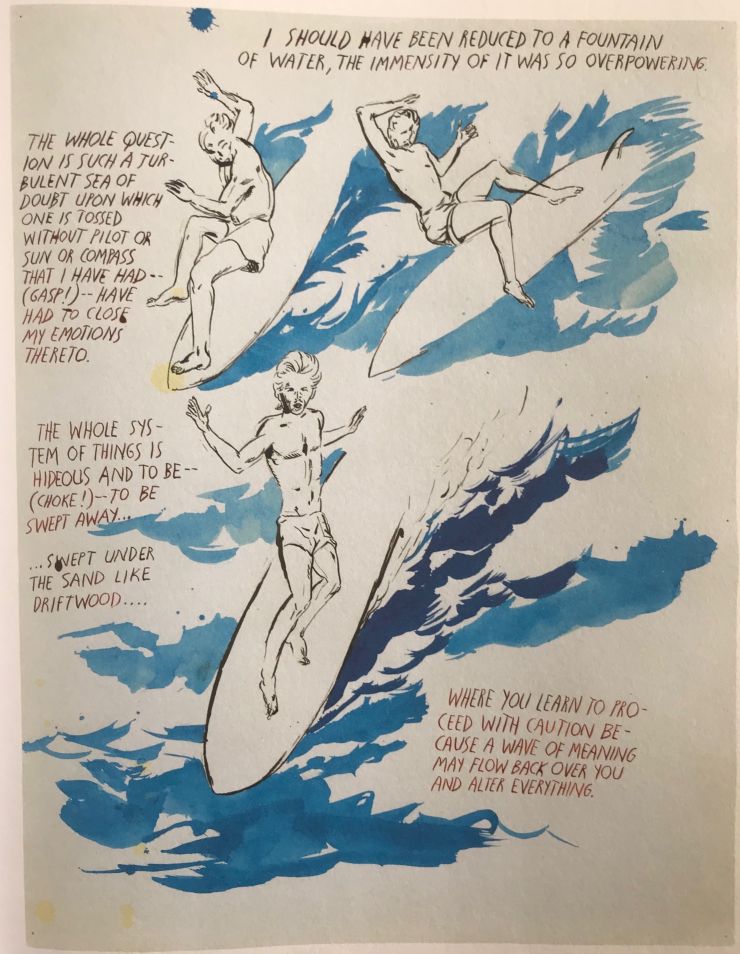

In recent years, Raymond has produced a flurry of surf paintings, most of them pitting a tiny surfer against a giant, spectacular wave. It’s impossible to not see the self-portrait: Raymond the artist, streaking across the pitching, heaving, throaty blue wall that is his hopes/dreams/ideas that ping around in his head. It’s also impossible to not see how he’s selected the perfect metaphor.

A brief history: The sixties surf craze brought crowds to once pristine and quiet surf breaks. Hardcore surfers rebelled. “Malibu is summer. . . . Now you have to share your summer vacations with everybody. Summer has had it,” goes the famous quote by Miki Dora. Professional surfing gained a foothold in 1976, with the birth of the International Professional Surfers (IPS), but that, too, provoked a backlash. For most surfers, the allure of wave riding was its dance, its communion with nature—not winners and losers. So began a debate: Surfing—sport or art?

For Raymond, it is clearly the art side that appeals. The ocean is fickle. There are no goals, hoops, finish lines. The wave is a fleeting, infinite blank canvas.

And big-wave surfing also appeals. Since the pioneering of Hawaii’s hallowed Waimea Bay in the late fifties, big waves have always attracted the characters, the cowboys, the loose cannons. Big-wave surfing enjoyed a giant leap forward in the mid-nineties with the birth of tow-in surfing: the Jet Ski assist made it possible for the rider to match the velocity of the looming monster wave. Surfers broke into the thirty-, fifty-, seventy-, and, most recently, hundred-foot range (see 100 Foot Wave docuseries on HBO).

Swell forecasting, too, has advanced the cause. Up until the mid-eighties, there was no accurate way to predict swells, hence surfers had to hover close to the beach to score the good days (and hence the stereotype of the unemployed surf bum). Enter Surfline, a 976 customer-toll number that gave the day’s surf report, plus a three-day wave forecast. Swell forecasting became increasingly precise in the late nineties, spawning what the surf media calls “surgical strikes”: big-wave riders flying halfway around the world to catch the apex of the swell, which sometimes lasts as briefly as a few hours.

Modern-day big-wave surfers are sort of bounty hunters. They spend a lot of time tracking swells on the internet. They have to be ready to pull the trigger on a moment’s notice. Their lives revolve around this thing they get to do only a handful of days per year, and their reputations are sometimes made on a single ride.

***

In 2010, I got the assignment to write a profile of Raymond for Monster Children, an Aussie magazine. Here’s a good chunk of it, expanded and condensed and revised for this volume:

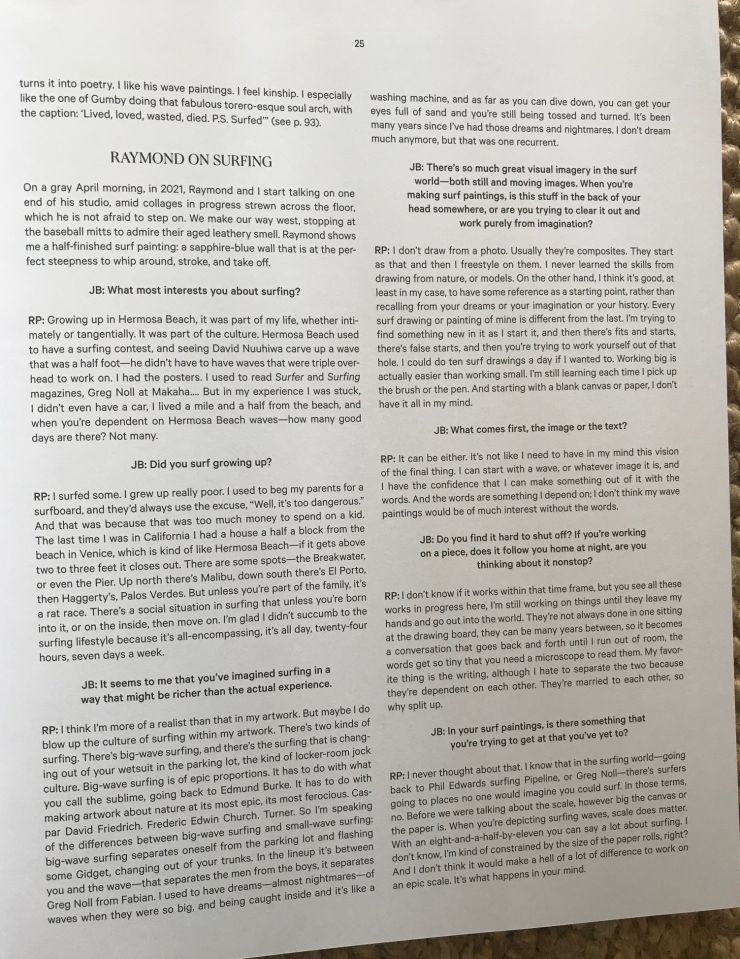

On a bright morning in his Venice Beach studio, Raymond Pettibon pondered his wave painting in progress. Seen from a high perch, a pier maybe, a vibrantly blue lefthander crests, the white lip about to hurl forward. An adept surfer might whip around and catch it in a single stroke, or perhaps none at all.

“The economy of means is one of the best things that drawing has going for itself,” he said between sips of coffee. “The great masters of drawing tend to have that elegant line. That tends to be an ongoing struggle with me within each individual work. I’ve done a number of waves before, but the point of view or take on it can get old. So I try to differentiate from that. When you can do something that seems new, the economy of the sublime—that’s what I’m trying to do.”

Raymond’s studio was a white-walled former furniture showroom on traffic-heavy Lincoln Boulevard. It looked as if it had been ransacked by the DEA. Dirty socks, weathered LPs, pulp novels, surf magazines, cruiser bikes, and vintage baseball mitts shared floor space with his dachshund mutt, Barely Noble. Strewn haphazardly about his worktable were newspapers, tubes of paint, lidless inkpots, a wooden baseball bat, loose CDs, an open bottle of rosé, and tortilla chips and salsa, all of which sat precariously close to or atop valuable half-finished drawings. Taped to the wall were works in progress: a buxom topless woman with a death mask; a man kissing an outstretched hand; a child’s red wagon; an apish arm and leg; a bent-over, naked woman with “This is too forward, Trick” scrawled above; and the feathery blue wave that he brooded over.

Raymond’s subject matter includes Charles Manson, surfers, baseball players, trains, vixens, homicidal teenage punks, Elvis, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, and the cartoon figure Gumby, who has the miraculous ability to walk into a book and enter a story (an alter ego, perhaps?). His stock-in-trade is the marriage, collision, and disconnection of image and text. Some pieces do this in a wry, straightforward manner; others are like great song lyrics: they could be interpreted a thousand different ways, and none would be wrong.

“My favorites are the ones that have some lyrical space beyond a strict interpretation,” he said, “the ones that I couldn’t put into any descriptive terms what I was doing.”

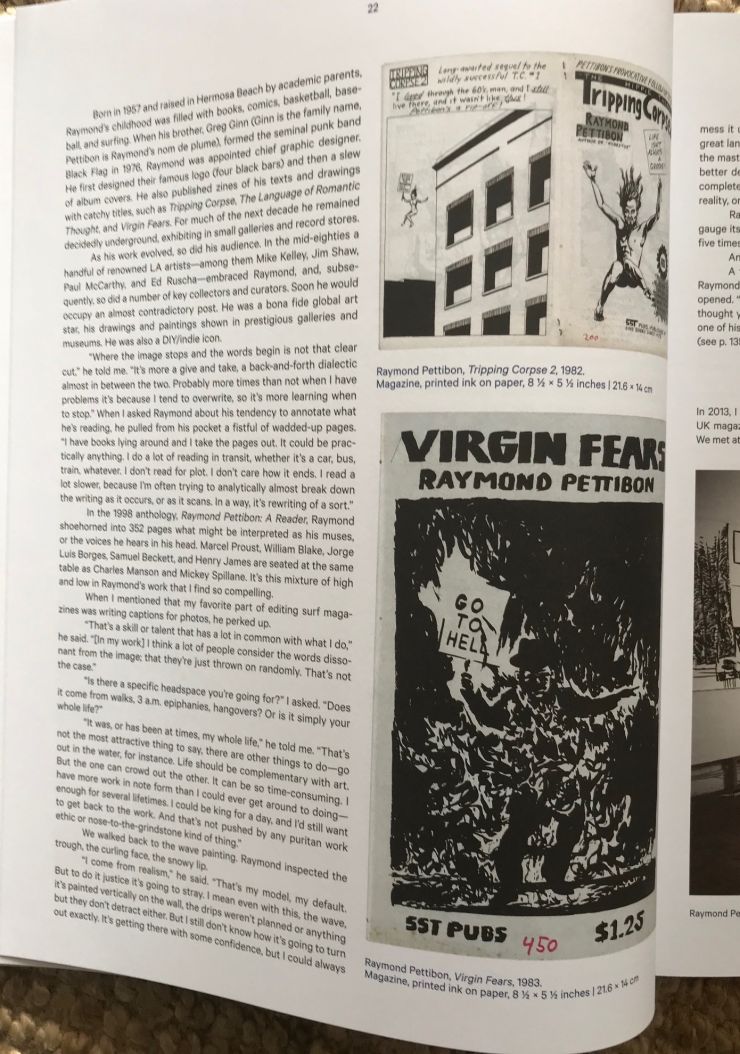

Born in 1957 and raised in Hermosa Beach by academic parents, Raymond’s childhood was filled with books, comics, basketball, baseball, and surfing. When his brother, Greg Ginn (Ginn is the family name, Pettibon is Raymond’s nom de plume), formed the seminal punk band Black Flag in 1976, Raymond was appointed chief graphic designer. He first designed their famous logo (four black bars) and then a slew of album covers. He also published zines of his texts and drawings with catchy titles, such as Tripping Corpse, The Language of Romantic Thought, and Virgin Fears. For much of the next decade he remained decidedly underground, exhibiting in small galleries and record stores.

As his work evolved, so did his audience. In the mid-eighties a handful of renowned LA artists—among them Mike Kelley, Jim Shaw, Paul McCarthy, and Ed Ruscha—embraced Raymond, and, subsequently, so did a number of key collectors and curators. Soon he would occupy an almost contradictory post. He was a bona fide global art star, his drawings and paintings shown in prestigious galleries and museums. He was also a DIY/indie icon.

“Where the image stops and the words begin is not that clear cut,” he told me. “It’s more a give and take, a back-and-forth dialectic almost in between the two. Probably more times than not when I have problems it’s because I tend to overwrite, so it’s more learning when to stop.” When I asked Raymond about his tendency to annotate what he’s reading, he pulled from his pocket a fistful of wadded-up pages. “I have books lying around and I take the pages out. It could be practically anything. I do a lot of reading in transit, whether it’s a car, bus, train, whatever. I don’t read for plot. I don’t care how it ends. I read a lot slower, because I’m often trying to analytically almost break down the writing as it occurs, or as it scans. In a way, it’s rewriting of a sort.”

In his 1998 anthology, Raymond Pettibon: A Reader, Raymond shoehorned into 352 pages what might be interpreted as his muses, or the voices he hears in his head. Marcel Proust, William Blake, Jorge Luis Borges, Samuel Beckett, and Henry James are seated at the same table as Charles Manson and Mickey Spillane. It’s this mixture of high and low in Raymond’s work that I find so compelling.

When I mentioned that my favorite part of editing surf magazines was writing captions for photos, he perked up.

“That’s a skill or talent that has a lot in common with what I do,” he said. “[In my work] I think a lot of people consider the words dissonant from the image; that they’re just thrown on randomly. That’s not the case.”

“Is there a specific headspace you’re going for?” I asked. “Does it come from walks, 3 a.m. epiphanies, hangovers? Or is it simply your whole life?”

“It was, or has been at times, my whole life,” he told me. “That’s not the most attractive thing to say, there are other things to do—go out in the water, for instance. Life should be complementary with art. But the one can crowd out the other. It can be so time-consuming. I have more work in note form than I could ever get around to doing—enough for several lifetimes. I could be king for a day, and I’d still want to get back to the work. And that’s not pushed by any puritan work ethic or nose-to-the-grindstone kind of thing.”

We walked back to the wave painting. Raymond inspected the trough, the curling face, the snowy lip.

“I come from realism,” he said. “That’s my model, my default. But to do it justice it’s going to stray. I mean even with this, the wave, it’s painted vertically on the wall, the drips weren’t planned or anything but they don’t detract either. But I still don’t know how it’s going to turn out exactly. It’s getting there with some confidence, but I could always mess it up. With this sort of thing I think of the image of Turner, the great landscape painter, painter of the sea, having himself strapped to the mast of a ship while it went into the storm, experiencing that as to better describe it. His sea paintings approximate or tend toward the complete abstract, but that’s still an act of realism, of understanding reality, or at least a sincere attempt to.”

Raymond stared at his wave. There was nothing in the frame to gauge its size, but judging by the look on his face it was giant, maybe five times overhead.

And he’d yet to even start in on the text.

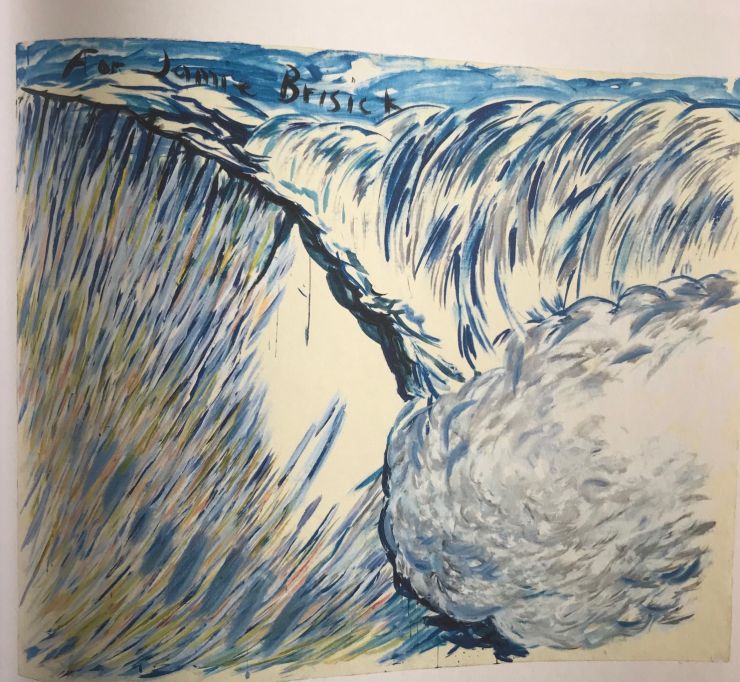

A few weeks later, Raymond’s gallery rep emailed saying that Raymond had enjoyed my visit, and that his New York show had just opened. “I just wanted to share this piece that is in Raymond’s show. I thought you would like to see it,” she wrote. Attached was a photo of one of his wave paintings. Written above the crest: “For Jamie Brisick.”

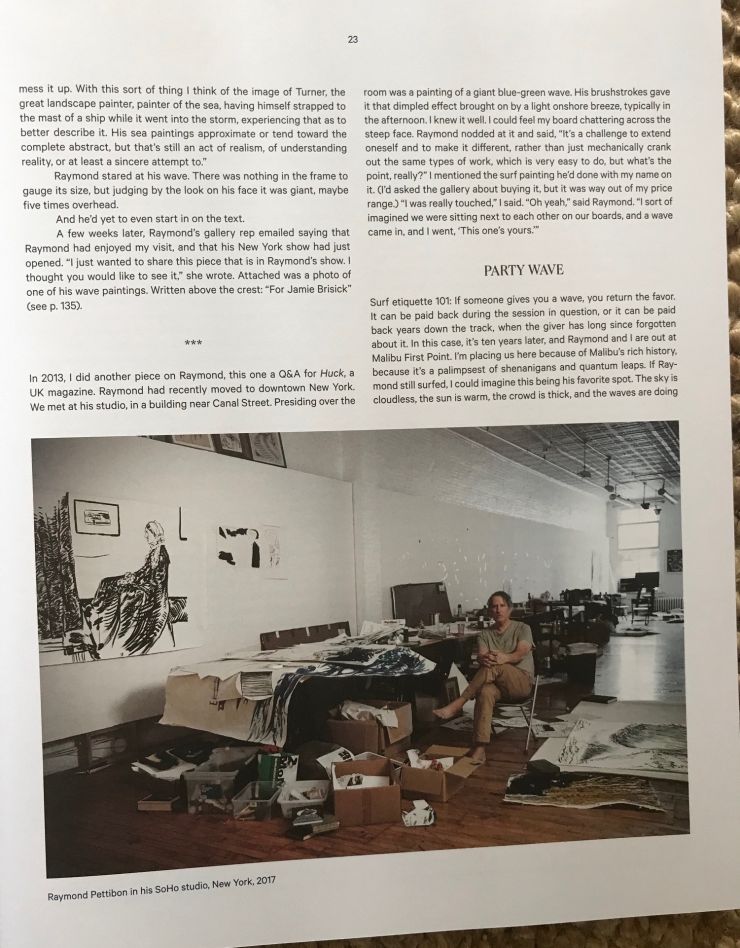

In 2013, I did another piece on Raymond, this one a Q&A for Huck, a UK magazine. Raymond had recently moved to downtown New York. We met at his studio, in a building near Canal Street. Presiding over the room was a painting of a giant blue-green wave. His brushstrokes gave it that dimpled effect brought on by a light onshore breeze, typically in the afternoon. I knew it well. I could feel my board chattering across the steep face. Raymond nodded at it and said, “It’s a challenge to extend oneself and to make it different, rather than just mechanically crank out the same types of work, which is very easy to do, but what’s the point, really?” I mentioned the surf painting he’d done with my name on it. (I’d asked the gallery about buying it, but it was way out of my price range.) “I was really touched,” I said. “Oh yeah,” said Raymond. “I sort of imagined we were sitting next to each other on our boards, and a wave came in, and I went, ‘This one’s yours.’”

Party Wave

Surf etiquette 101: If someone gives you a wave, you return the favor. It can be paid back during the session in question, or it can be paid back years down the track, when the giver has long since forgotten about it. In this case, it’s ten years later, and Raymond and I are out at Malibu First Point. I’m placing us here because of Malibu’s rich history, because it’s a palimpsest of shenanigans and quantum leaps. If Raymond still surfed, I could imagine this being his favorite spot. The sky is cloudless, the sun is warm, the crowd is thick, and the waves are doing what First Point does, which is peel with machine-like precision for a good hundred yards.

I see Raymond and me straddling our boards side by side, eyes fixed on the carpet of shimmering blue that stretches to the horizon. A sweet, head-high wave looms and I turn to Raymond and say, “This one’s yours.” He nods, as if to say, “I remember,” wheels his board around, paddles, and pops to his feet and angles toward the pier. What he doesn’t know is that I’ve organized a surprise party, or let’s call it a “surprise party wave,” in which friends, colleagues, a critic, and a ghost will drop in, share the wave for a few beats, then kick out the back, leaving Raymond to his elegant line:

“Raymond always wanted to be a surfer,” says the musician Mike Watt. Raymond made the art for Watt’s first record with his band Minutemen. They’ve been friends ever since. “He obviously has a passion for it. To me, I think it’s this connect. You don’t have to have the correct words for this interface with reality. In fact, you’re part of it. You’re trying to ride it, and you’re trying to channel this force. He likes this idea, the things that make us know we’re alive. It seems this is part of his work, ‘How do I know I’m alive?’ Almost a Greek thing of ‘How do we know what we know?’ kind of shit. He likes the mystery, too, and the observer being part of the work.”

“I think Raymond’s surf artwork is tongue-in-cheek,” says the artist, curator, and filmmaker Aaron Rose. “Not to anger the surfers in the crowd, but I don’t know if it’s so much a homage or respect as it is a metaphor.”

“There’s no way on earth that Raymond has devoted as much paper as he has to surfing if it was just purely tongue-in-cheek,” says the artist John Millei. “It’s kind of like Jasper Johns and a lot of the great ironists as artists, that their work is always the very thing in its most sincere form that is also self-reflective. And in being self-reflective and self-conscious, it is ironic. And I think that is Raymond’s genius. Because Raymond is an elusive cat, right? He is such a genius at self-mythologizing. And he knows full well the place for him to reside is in the liminal space between things. He doesn’t really make paintings. He doesn’t really make drawings. They’re not paintings. They’re not drawings. They’re works on paper. Everything about his practice is about living in these liminal spaces between things, including all the content.”

For the last half century, the SoCal native Craig Stecyk has documented and influenced the surf, skate, and snowboarding cultures, most notably the Dogtown scene of the 1970s. When I told him about Raymond’s party wave he said, “Let me write something.” I like to imagine that he paddles into the wave, pops to his feet, draws a scroll from the sleeve of his wetsuit, and reads aloud from it—

Raymond Ginn Pettibon predicates his discourse with expressed pronouncements that he is not a surfer. Nor is he a draftsman, or a locomotive enthusiast. Nor a punk ingenue, baseball player, cartoonist, dreamscape desperado, politico, musician, Nietzschean poststructuralist, filmmaker, Mansonite, or cinema director. Throughout all the denials, Pettibon steadfastly remains both a devoted father as well as an introspective son.

In the chaotically forlorn ruinous expanse of Raymond’s atelier there is no discernible order. Reams of torn pages, bats, balls, swim fins, volumes of scientific inquiry, and the like are equally abandoned across the floor. The previously described jetsam is treated no differently than the haphazardly tossed artworks that characteristically also land among the drifting detritus. Interspersed throughout are incidental artifacts, which periodically are summoned forth in support of the effort. Pettibon draws as he thinks. It is a furiously constant Gesamtkunstwerk.

A studio pitching machine intermittently heaves erratically aimed ninety-mph beanballs. Don’t crowd that plate. Pay attention. Cogito, ergo sum isn’t the fundamental premise. Rather it’s I draw, therefore I think . . . Duco, ergo cogito. The rhythm of the line dictates disembodied abstracted veracities. Every tale in Pettibon’s milieu is irresistibly persuasive. None is based on any single correct Rubik’s Cube–like formula. True solutions do not exist. Life’s experiences are farcically a tabula rasa. Oblivion forges illusionistic responses as a defense against the echoes of the void. But sailing off the charts is the essence of navigation.

The artist Marcel Dzama met Raymond at an art dinner about a decade ago. They sat next to each other and fidgeted awkwardly. When dessert landed on the table Raymond pulled out a pen and drew a breast spraying milk toward it. Marcel took the pen and added a little character trying to catch the milk in his mouth. So began several drawing and painting collaborations.

“I really think Raymond is the William Blake of our time where he’s just as talented in his poetry as he is in his artwork,” says Marcel. “The two together are such a great combination; they improve each other. He comes alive when he’s working. And we communicate better when we’re not talking but just drawing at the same time, kind of like musicians improvising together.

“Raymond writes in notebooks and books, and he’d always throw them out, and I’d take them from the trash to check them out and see what he was writing. It was fascinating to see. That creative process of how he can just take a little morsel from, I think it was Paradise Lost, and just run with it, and go to this other world with it—it’s really inspiring.”

“Pettibon’s work is raw and none too precious,” says Scott Hulet, a longtime editor of The Surfer’s Journal. “It looks naive and honest, like ballpoint pens on a Pee-Chee folder. The wave forms are correct, and if the artist didn’t surf, he knew surfing. Pettibon’s use of those high-minded, paraphrased quotes elevates and complexifies the compositions. Surfers like having their life’s obsession anchored with thoughtful ballast.”

“I think for Raymond surfing is a big sustaining idea,” says the art critic Dave Hickey. “As Lou Reed said in ‘Heroin,’ ‘It’s my wife and it’s my life.’ Surfing is a primal metaphor. If you have a dream about success, it’s about riding a big wave. If you have an anxiety dream like I did, and you’re having dinner on La Cienega, and you look up and there’s a forty-foot wave above your head . . . It’s a primal metaphor that kind of gets into your life.”

Rebel surfer Miki Dora (aka “Da Cat,” “the Black Knight,” “Malibu Mickey,” “the Fiasco Kid”) died in 2002, but if he were still alive he might say, “My whole life is this wave. I drop in, set the thing up, and behind me all this stuff goes over my back; the screaming parents, teachers, police, priests, politicians—they’re all going headfirst into the reef. And when it starts to close out, I pull out the back, pick up another wave, and do the same goddamn thing. Raymond’s art practice is something similar, but while we surfers fly past this cascade of worldly ills, Raymond catches it square on the head, swims in it, and turns it into poetry. I like his wave paintings. I feel kinship. I especially like the one of Gumby doing that fabulous torero-esque soul arch, with the caption: ‘Lived, loved, wasted, died. P.S. Surfed.’”

Raymond on Surfing

On a gray April morning, in 2021, Raymond and I start talking on one end of his studio, amid collages in progress strewn across the floor, which he is not afraid to step on. We make our way west, stopping at the baseball mitts to admire their aged leathery smell. Raymond shows me a half-finished surf painting: a sapphire-blue wall that is at the perfect steepness to whip around, stroke, and take off.

JB: What most interests you about surfing?

RP: Growing up in Hermosa Beach, it was part of my life, whether intimately or tangentially. It was part of the culture. Hermosa Beach used to have a surfing contest, and seeing David Nuuhiwa carve up a wave that was a half-foot—he didn’t have to have waves that were triple overhead to work on. I had the posters. I used to read Surfer and Surfing magazines, Greg Noll at Makaha . . . But in my experience I was stuck, I didn’t even have a car, I lived a mile and a half from the beach, and when you’re dependent on Hermosa Beach waves—how many good days are there? Not many.

JB: Did you surf growing up?

RP: I surfed some. I grew up really poor. I used to beg my parents for a surfboard, and they’d always use the excuse, “Well, it’s too dangerous.” And that was because that was too much money to spend on a kid. The last time I was in California I had a house a half a block from the beach in Venice, which is kind of like Hermosa Beach—if it gets above two to three feet it closes out. There’re some spots—the Breakwater, or even the Pier. Up north there’s Malibu, down south there’s El Porto, then Haggerty’s, Palos Verdes. But unless you’re part of the family, it’s a rat race. There’s a social situation in surfing that unless you’re born into it, or on the inside, then move on. I’m glad I didn’t succumb to the surfing lifestyle because it’s all-encompassing, it’s all day, twenty-four hours, seven days a week.

JB: It seems to me that you’ve imagined surfing in a way that might be richer than the actual experience.

RP: I think I’m more of a realist than that in my artwork. But maybe I do blow up the culture of surfing within my artwork. There’s two kinds of surfing. There’s big-wave surfing, and there’s the surfing that is changing out of your wetsuit in the parking lot, the kind of locker-room jock culture. Big-wave surfing is of epic proportions. It has to do with what you call the sublime, going back to Edmund Burke. It has to do with making artwork about nature at its most epic, its most ferocious. Caspar David Friedrich. Frederic Edwin Church. Turner. So I’m speaking of the differences between big-wave surfing and small-wave surfing: big-wave surfing separates oneself from the parking lot and flashing some Gidget, changing out of your trunks. In the lineup it’s between you and the wave—that separates the men from the boys, it separates Greg Noll from Fabian. I used to have dreams—almost nightmares—of waves when they were so big, and being caught inside and it’s like a washing machine, and as far as you can dive down, you can get your eyes full of sand and you’re still being tossed and turned. It’s been many years since I’ve had those dreams and nightmares. I don’t dream much anymore, but that was one recurrent.

JB: There’s so much great visual imagery in the surf world—both still and moving images. When you’re making surf paintings, is this stuff in the back of your head somewhere, or are you trying to clear it out and work purely from imagination?

RP: I don’t draw from a photo. Usually they’re composites. They start as that and then I freestyle on them. I never learned the skills from drawing from nature, or models. On the other hand, I think it’s good, at least in my case, to have some reference as a starting point at least, rather than recalling from your dreams or your imagination or your history. Every surf drawing or painting of mine is different from the last. I’m trying to find something new in it as I start it, and then there’s fits and starts, there’s false starts, and then you’re trying to work yourself out of that hole. I could do ten surf drawings a day if I wanted to. Working big is actually easier than working small. I’m still learning each time I pick up the brush or the pen. And starting with a blank canvas or paper, I don’t have it all in my mind.

JB: What comes first, the image or the text?

RP: It can be either. It’s not like I need to have in my mind this vision of the final thing. I can start with a wave, or whatever image it is, and I have the confidence that I can make something out of it with the words. And the words are something I depend on; I don’t think my wave paintings would be of much interest without the words.

JB: Do you find it hard to shut off? If you’re working on a piece, does it follow you home at night, are you thinking about it nonstop?

RP: I don’t know if it works within that time frame, but you see all these works in progress here, I’m still working on things until they leave my hands and go out into the world. They’re not always done in one sitting at the drawing board, they can be many years between, so it becomes a conversation that goes back and forth until I run out of room, the words get so tiny that you need a microscope to read them. My favorite thing is the writing, although I hate to separate the two because they’re dependent on each other. They’re married to each other, so why split up.

JB: In your surf paintings, is there something that you’re trying to get at that you’ve yet to?

RP: I never thought about that. I know that in the surfing world—going back to Phil Edwards surfing Pipeline, or Greg Noll—there’s surfers going to places no one would imagine you could surf. In those terms, no. Before we were talking about the scale, however big the canvas or the paper is. When you’re depicting surfing waves, scale does matter. With an eight-and-a-half-by-eleven you can say a lot about surfing. I don’t know, I’m kind of constrained by the size of the paper rolls, right? And I don’t think it would make a hell of a lot of difference to work on an epic scale. It’s what happens in your mind.