Books About Surfing That I’ve Read and Very Much Enjoyed

At the Mansplainers Anonymous Meeting (on KelpJournal.com)

At the Mansplainers Anonymous meeting we were given a maximum of twenty-five words to express our feelings

Exceed twenty-five and you were put on coffee duty

By the end of the meeting you’d have a circle of empty folding chairs

And a bunch of men huddled around the coffee pot

Arguing over how to make the perfect pot of coffee.

At the Mansplainers Anonymous meeting we went into extra innings

Overtime

Penalty kicks

They’d begin on a Thursday at 5pm

And still not be finished the following Monday.

At the Mansplainers Anonymous meeting we refused to call it MA

We didn’t believe in acronyms

We had an affinity for the multisyllabic

Though we were working on that.

At the Mansplainers Anonymous meeting we debated intermittent fasting versus time-restricted feeding, Netflix versus Hulu.

At the Mansplainers Anonymous meeting we talked about Van Nuys

Chad said he had a blowout on the 101 over there in Van Nuys

Bruce said, “In Van Nuys, you can just say, ‘I had a blowout on the 101 in Van Nuys,’ you don’t need the ‘over there,’ the ‘over there’ is kind of hurtful to Van Nuys, don’t you think?”

Chad argued that there are places where things happen ‘in’ and there are places where things happen ‘over there in,’ and Van Nuys was an ‘over there in,’ especially considering he was driving a ‘67 El Camino, and that while they were fixing his tire he went around the corner to a topless bar called the Candy Cat where he met a girl named Licorice who he exchanged numbers with and was hoping to see on the weekend

“So in the context of the larger story, if you’d have just let me finish, you’d see that ‘over there in Van Nuys’ is much better than just ‘in Van Nuys’”

“What’d we say about ‘let me finish’?” said Bruce

“Oh shit,” said Chad

The room laughed. There were many things you were not allowed to say at a Mansplainers Anonymous meeting. One of them was “let me finish.”

At the Mansplainers Anonymous meeting we were encouraged to sit in on other twelve-step meetings

So on a Wednesday evening at 6pm I found myself tucked into the Calabasas High School gymnasium with my brethren over there at Name Droppers Anonymous

They were a lot like us, and nothing like us

A redheaded Gen Zer shared how she’d dated ___________, and while dating him she’d met ______________, who introduced her to ______________, and now she’s having a show at his art gallery. Her show features photographs of famous people dining around LA, but inspired by the program, she doesn’t feature the actual famous people, but rather the aftermath of their meals. For example, she said, the caption might read “__________ and _________, Giorgio Baldi, October 9, 2015,” but the photo just shows a couple of pomodoro-smeared plates and the four empty martini glasses from _________, who we now know via testimony from ______________ was a heavy drinker, despite his handsome looks and excellent performances, most recently alongside _________________ in Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood.

At the Mansplainers Anonymous meeting, Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions, votive candles, a key chain, a dog-eared copy of Men Explain Things to Me by Rebecca Solnit.

At the Mansplainers Anonymous meeting

Actually, after the Mansplainers Anonymous meeting

I brought the fellas out to my car

The engine pinged when driving up steep hills, and it had been burning through oil like there was no tomorrow

This was at the North Hollywood meeting

Filled to the gills (as the expression goes) with washed-up actors and stuck screenwriters

Parked in the adjacent Gelson’s lot, hood up, there was at first about fifteen of us

But then something beautiful happened

More men started showing up, dozens weighing in on what might be the culprit

Bad spark plugs, worn out piston rings, maybe the transmission

It was like a tailgate party, but with everyone gathered around the hood.

And while a tailgate party involves many cars, this was just one, my 2003 Mercedes G-wagon, and what by the end of the night must have been a good hundred-and-fifty of us.

In The Malibu Parking Lot (in Heavy Traffic III)

In the Malibu Parking Lot

by Jamie Brisick

In the Malibu parking lot, there were rules

Rule #1: Don’t drop in

Rule #2: Share your weed

Your wax

If you have a second beer, pass it along

Tomorrow you’ll be thirsty

Rule #3: Acknowledge Malibu Carl. Say hi to Parking Lot Teddy

Rule #4:

(Not so much a rule but an understanding)

There is no problem so big or complicated that it cannot be run away from

At the Malibu Wall, we chased nose rides, blow jobs, beer

At the Malibu Wall, we had no health insurance

At the Malibu Wall, a fin chop could take the whole thing down

As it had for Parking Lot Teddy

Not his own fin but a freshman from Pepperdine’s

Who’d been surfing less than a year

22 stitches

$3700 at St. John’s

Now Teddy sleeps in his van

In the alley behind Ralphs

At the Malibu Wall, there was blood

At the Malibu Wall, it was not Teddy’s

At the Malibu Wall, last we heard the Pepperdine kid had taken up golf

In the Malibu parking lot, I surrendered my virginity to a bronzed lioness of a regular foot named Ashley. Her skin smelled of Coppertone. Her left-go-right bottom turn was fierce. For a summer we lived in her beater van, subsisting on Jack in the Box tacos and Tecates stolen from the back of the liquor store. She called me dude, as in “Slow down, dude,” “Little to the left, dude,” “Try again, dude,” “Okay, D minus for today, now let’s go get a wave, dude.”

In the shimmering waters of Malibu, my mascara ran, my lipstick sprinted, my facelift pole-vaulted, my raw and unvarnished self stood soft and vulnerable across the three-foot peelers. The afternoon sun was a French kiss. The light onshore wind carried the wisdom of the ancients. Neptune three-pronged me the way a cattle rancher brands his cow. Magellan slapped me and said, “Not a 50-foot nose ride but a 360-degree odyssey, an entire life. So less of the rum and more of the captain’s log, if ya know what I’m sayin’.”

At the Malibu Wall, we hid behind dark sunglasses

And spoke with our hands

At the Malibu Wall, we traded sex

For a chocolate shake, large fries, and a double cheeseburger

At the Malibu Wall, it happened in the men’s room

At the Malibu Wall, Parking Lot Teddy guarded the door

In exchange for half the shake

And a couple bites of the cheeseburger

At Malibu Wall, we didn’t use fancy words like ‘transactional’

At the Malibu Wall, we were hungry

And we ate

In the Malibu parking lot, I wrestled with my masculinity, which spoke in a gravely, Scotch-and-Camel-non-filters tone, and at one point grabbed me by the shoulder in a way that my 2021 self found aggressive. I said, ‘Please remove your hand from my shoulder.’ My masculinity removed its hairy hand, cackled, shrugged its macho shoulders, and said, ‘What the hell happened to you?

In the Malibu parking lot, the rear hatch of a ’77 Econoline popped open. Out flew a Nike. Then a wetsuit. Then an MSA jacket. Then another Nike. Then an 8-foot Liddle displacement hull, which landed nose first, making it something like a 7’9” or 7’8” “And stay the fuck away from me you piece of shit,” shouted Ashley. I crawled out the passenger side door, retrieved my things, made my way towards the pier.

At the pearly gates of Malibu, I poured out confessions (hiding six-packs in my backpack, not sharing joints with Malibu Carl, borrowing Grossrider’s prized 9’ Yater without asking). There was a tribunal of sorts involving Bosco and Trace and Parking Lot Teddy. They told me to hold tight, disappeared into Teddy’s van, shut the door, re-emerged 20 minutes later. “Carton of cigarettes for Carl, bottle of tequila for Teddy. I’m on the wagon this week so basically I get to drop in on you every chance I get,” said Trace. I nodded compliantly. He pointed seaward. A sparkling head-high set peeled across First Point. “Carry on,” he said.

In the Malibu parking lot, I managed to locate my inner adolescent. He emerged from the men’s room with bloodshot eyes and beer on his breath. “I miss you,” I said. He looked over his shoulder then back at me. With a confused expression he said, “Do I know you?”

In the Malibu parking lot, I remembered Seaweed, who called it the workajerka.

“Every job I ever had just seemed to grab me by the back of the neck and drop me somewhere inland. I don’t do the workajerka.”

Seaweed lived out of his car, a ‘57 Comet wagon. He did not believe in deodorant (“That’s our body’s irrigation, you can’t block it up.”) He believed wholeheartedly in bongloads (“I like to put ice in there. End of a long hot summer day on the beach, an ice water bong, life doesn’t get any better than that”).

I remembered John, who’d go on to a successful art career. Malibu was part of his narrative, his education, the thing he left behind.

“One day I was pulling out of the lot and I just knew, you know? I drove out real slow, took it all in. I turned south on PCH and never went back.”

I remembered Charlie, a regular foot with a big frontside carve. Charlie was reluctantly sober. In a low ebb, nursing yet another hangover, I said, “Charlie, I think I might need to get sober.”

Charlie rested his hand on my shoulder. “Whatever you do, don’t get sober. The sober you will just be another kind of annoying that no one will want to be around.”

It was Charlie who also said: “You start hanging out in the Malibu parking lot…and you become the Malibu parking lot.”

In the Malibu parking lot, I spilled oil, blood, ink, semen, Mr. Zog’s Sex Wax

In the Malibu parking lot: ghosts

The ghost of Miki, Moondoggie, Tubesteak, Lance, Dewey, The Enforcer, Fruit Loop, Head and Shoulders, Seaweed

In the Malibu parking lot, beer was consumed, facts were muddled, words were slurrred

In the Malibu parking lot, summer’s ready when you are

In the Malibu parking lot, in the summer, in the city

In the Malibu parking lot, and the livin’ is easy

In the Malibu parking lot, boys in bikinis, girls in surfboards

In the Malibu parking lot, everybody’s rockin’

In the Malibu parking lot, an American songbook

In the Malibu parking lot, Woody Guthrie was a regular foot

JayZ a goofy

In the Ma

In the Malibu parking lot, sex in the back of Steve and Ashley’s ‘77 Econoline van, Bizarre Love Triangle by New Order on the stereo, wet wetsuits at our feet, the rail of Steve’s 8’2” Anderson pushing into my hip, the taste of Starbucks and cigarettes on Ashley’s lips

In the Malibu parking lot, we never plan these things

In the Malibu parking lot, Ashley says she loves me

In the Malibu parking lot, Steve comes back from Mexico on Friday

In the Malibu parking lot, I am not quite a red belt, but I’ve got a few tae kwon do moves up my sleeve

In the Malibu parking lot, Steve’s a jiu jitsu black belt

In the Malibu parking lot, I have an uncle up in San Francisco who keeps telling me to visit

In the Malibu parking lot, a west swell coming next week

In the Malibu parking lot, west swells like Ocean Beach

In the Malibu parking lot, a note slid under the windshield wiper of Steve and Ashley’s ‘77 Econoline van

In the Malibu parking lot: I was a hippie I was a burnout I was a dropout I was out of my head

In the Malibu parking lot: Two sides to every story

In the Malibu parking lot: Somebody had to stop me

In the Malibu parking lot: I’m not the same as when I began

In the Malibu parking lot: Punk rock landed with a splash

Clear boards/black wetsuits turned into leopard-spotted boards/pink and purple wetsuits

In the Malibu parking lot: Abracadabra

In the Malibu parking lot: Paris Hilton, Britney Spears, and Malibu Barbie

Puff a joint

Behind the lifeguard tower

Lots of sunscreen, dark sunglasses, wide-brimmed hats

In the Malibu parking lot: Development was arrested, growth was stu

In the Malibu parking lot: In the maw of Peter Pan

At the pearly gates of Malibu, I felt the black dog, the mean reds, the Nausea, the dark night of the soul at 3am, though it was 4pm, and sunny, and 81 degrees.

At the pearly gates of Malibu, I called upon the holy texts of Pema, I clenched my fist the way Tony Robbins would, I promised myself I’d study The Work of Byron Katie.

At the pearly gates of Malibu, Timmy was kind enough to lend me his 11’ glider, decorated in polka dots, and I paddled out on it, imagining that they were not polka dots but pills (Xanax, Zoloft, Wellbutrin) and that the waves were not oceanic waves but the blue waves of the Democratic party, scooping me up and gli

In the Malibu parking lot, I saw a Debbie Harry-looking woman wearing a Malibu sweatshirt. I said, “Where’d you get it?” She said, “Rule number one: Never ask ‘where’d you get it.’” I said, “Fuck off. Tell me where you got it.” She blew a bubble. As it popped on her Chapstick-glossed lips I was hit with a waft of grape Bubblicious. Nostalgia floored me. Coppertone. Wine coolers. A keg party in Woodland Hills. A Dead Kennedys show at the Whiskey. I said, “Didn’t we have sex in the backseat of a Volkswagen Rabbit behind the Jack in the Box in Agoura in, like, 1982?” She said, “Brothers Marshall.” I said, “You had sex with Brothers Marshall in the backseat of a Volkswagen Rabbit behind the Jack in the Box in Agoura?” She said, “No, idiot. I got the sweatshirt at their new shop, down there by Duke’s, next to the breakfast burrito joint, near the hardware store, a couple doors down from Malibu Divers, which, by the way, is also the title of a really atrocious porn film, made right around 1982. Maybe you know it?”

In the Malibu parking lot, tequila, vodka, Tecate, Diet Coke. In the Malibu parking lot, tomfoolery, Tom Curren, Thomas Campbell, Tomás the Argentinian parking lot attendant. In the Malibu parking lot, Marilyn and JFK, Gidget and Moondoggie. In the Malibu parking lot, graffitied on the wall: “Without art we are but monkeys with smart phones.” In the Malibu parking lot, an 8’6” Yater swapped for a 6’10” Skip Frye. In the Malibu parking lot, sea gulls attack a Jack in the Box bag. In the Malibu parking lot, high tide, high noon, high times, hi Mom. In the Ma

At the Church of the Open Sky that is Kiddie Bowl, I did not say three Our Fathers and six Hail Marys but rather banged seven lips and pulled into nineteen tubes

In the Cathedral of Forever Facing Seaward that is First Point, Nate dropped in on Randall, Randall called him a shoulder shark, and the N-word, and punched him in the face

They took it to the beach

Hurl a whole watermelon at the ground and that’s what it sounded like, Nate’s fists banging into Randall’s wet torso and face and head

Randall slithered free, punched the fin out of his board, held it up like a knife

Nate was fighting for much more than the wave

Or the bully that was Randall

Pinning Randall and his fin-wielding hand to the ground, Nate punched and punched

The next day Randall showed up with a gun

Guns don’t hide so well in boardshorts

In the Malibu parking lot, a row of cop cars

Randall in handcuffs

Silent applause from all of us who’d had run-ins with Randall

Randall disappeared for a few days

Nate, sadly, never came back

In the Wild West that was Malibu that summer

Frontier justice prevailed

But not really

“Ashley Bickteron, Unflinchingly Honest About His Work and Illness” in NY Times

AN APPRAISAL

Ashley Bickerton, Unflinchingly Honest About His Work and Illness

Last words (and works) of the artist diagnosed with ALS in 2021. A devoted surfer, he chose to live remotely in Bali, away from the buzz. It found him anyway.

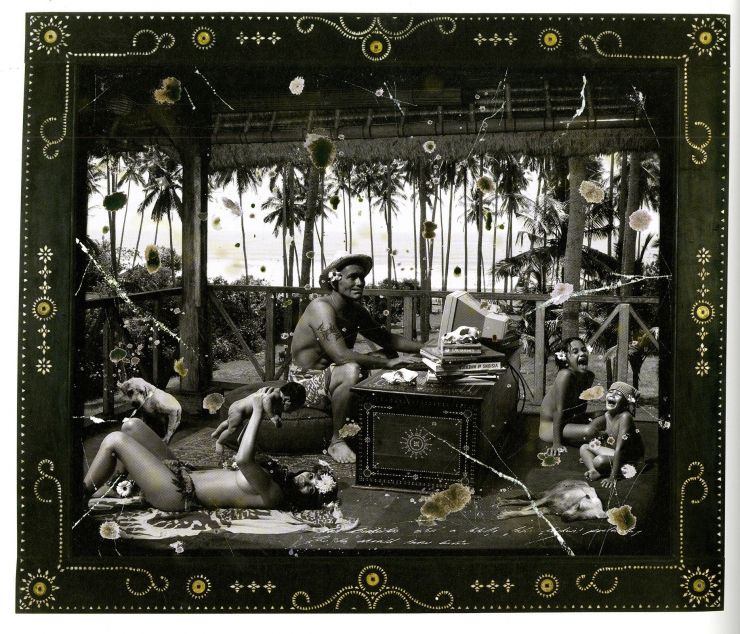

“I can’t think of another artist who was both brilliant on canvas and on a surfboard,” said Paul Theroux, the writer. He was speaking of one of the artists he most admired, Ashley Bickerton, and these words of Theroux’s inspired me to plan a trip to his home: “If Gauguin had caught some waves in Tahiti then I think we’d have an apt comparison.”

Ashley rose to prominence in the mid-1980s with ironic, abstracted constructions focused on ideas of consumerism, identity and value. He had been diagnosed with ALS in 2021, and by July, when I finally visited him in Bali, he needed help bringing food to his mouth, and he could no longer paint. But there was not an ounce of self-pity. “I consider myself enormously lucky,” said the artist from his power wheelchair. “It’s an incredible luxury that I can sit here on my big veranda on the hill overlooking the Indian Ocean, spend time with my wife and daughter, work on my computer, think, dream and put my life in order.”

He was courageous, graceful, eloquent, inspired. And full of gallows humor. After a Thai feast at his sprawling compound on the southern tip of Bali, I gestured toward his wife and three-year-old daughter, who were playing on the sofa, his paintings and sculptures surrounding us, his swimming pool and spectacular ocean view, and said, “What a beautiful life you’ve made for yourself.” With a rosy-cheeked grin he said, “What’s left of it.”

Ashley died on Nov. 30. He was 63.

I had come to interview him as an adjunct to his getting his affairs in order. We’d meet in the early afternoon in his crow’s nest of an office. Seated at his desk, often sipping a Coke through a straw, he’d excitedly show me the fantasy waves he’d been building in Photoshop (a devout surfer, ALS had robbed him of his daily fix). From there we’d move on to weightier stuff — his biography, his body of work, his family. He did not want to get into the details of his diagnosis. His face lit up when he spoke about the paintings he was making for his forthcoming exhibition in New York.

“I had two big shows in New York earlier this year,” he told me. “My whole plan had been to throw everything I had into these, then come back here and quietly rot away and die on my hill. Then Larry Gagosian stepped into the picture and ruined all my plans.”

He was referring to his recent good news. Gagosian had picked him up, scheduling his first solo show with the gallery in 2023. The announcement created buzz in the art world: “Over the past few years, Bickerton has brought his practice full circle, synthesizing its heterogeneous modes and gestures into an all-encompassing visual language.”

“It was exhilarating and much welcomed,” said Ashley. “But I suddenly realized that I’m going to be scrambling to the edge of the precipice without a moment to breathe.”

A Man of Two Worlds

Born in 1959 in Barbados to a clinical psychologist mother and a linguist father, Ashley’s childhood was itinerant, with stints in South America, the Caribbean, West Africa, England and eventually Hawaii, where he came to surfing at age 12. At the famed California Institute of the Arts, he studied with the conceptual artists Barbara Kruger and John Baldessari. “It was a real mind shake-up,” said Ashley. “I was basically told that everything I believed was rubbish, and that I should be ripping up bits of cardboard and locking myself in footlockers overnight and bending every rule.” He spent 12 years in New York, rising to fame in the 1980s alongside fellow Neo-Geo (for Neo-geometric conceptualism) artists Jeff Koons, Peter Halley and Meyer Vaisman.

Ashley’s early work drew from pop art, Op Art and minimalism. He became known for a mixed-media series titled as “Self-Portraits,” as “Commercial Pieces” or as “Anthropospheres,” composed of screen printed images of corporate logos. He even invented a brand for himself, SUSIE (full name: Susie Culturelux), which he said would double as an artistic signature for future art historians. In a clunky 1987-88 wall piece titled “Tormented Self-Portrait (Susie at Arles) #2” — there’s a version in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection — his Susie logo floats amid a sea of logos, among them Nike, Con Edison, Marlboro, Renault and Fruit of the Loom.

“My identity was forged in New York, my language, my sense of being an outsider,” said Ashley. “But New York never quite fit. I’m a tropics man. I was at odds with the Northeast winter.”

In 1993 he moved to Bali, where he resided until his death. Reading aloud from a manifesto he’d written some years back, he said, “Choose your material carefully. Avoid too many art fairs. And travel, limit your footprint and disappear.”

I first encountered Ashley via one of his self-portraits in Surfer’s Journal magazine in the late ’90s. Surrounded by palm trees, a near-naked woman, kids, dogs, tropical rapture, he was working bare-chested at an outdoor desk. He appeared robust, godlike. Like Gauguin in Tahiti or Peter Beard in Kenya, it was a portrait of an exotic, far-flung, fecund life. It made me wonder what the hell I was doing living in the East Village. When I told Ashley this in July, he chuckled.

“That was a sendup,” he said.

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“That was a request for a bio photo from Dakis Joannou’s DESTE Foundation [for Contemporary Art, a nonprofit]. I was gleefully, intentionally shoveling horseshit. But the photo got around, and people believed it. So I ran with it.”

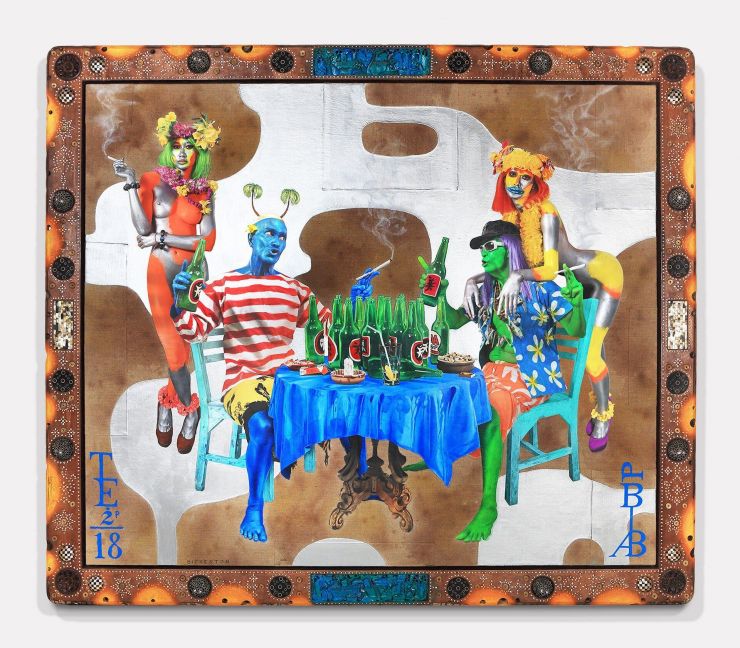

Ashley’s work includes painting, photography, sculpture, assemblage and every combination therein. He melds beauty and grotesquerie, playfulness and brutality. “A friend said that when I’m serious I come off as joking, but when I’m joking I’m dead serious,” Ashley told me. “That play has been central to my work.”

His “Blue Man” series plops a blue-skinned tourist into clichéd tropical settings. “He’s an avatar for the archetype of the 20th century antihero escapee from the annals of the 20th century canon of literature,” explained Ashley. “But now he’s adrift in an alienating 21st century world, trying to live his Gauguin fantasy.”

I told him I thought it a bold move, living remotely, stepping away from “the conversation.”

“If you think of the art world as a marketplace, we artists are the suppliers,” Ashley said. “And if everyone’s farming the same soil, it creates a much more monocultural, homogeneous marketplace. But if you go further afield — both mentally and geographically — you can affect the psychology, you can bring back to market something of interest that’s harder to come by.”

Read the full story at https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/12/arts/design/ashley-bickerton-artist-appraisal-als.html

“The Dazzling Blackness” for Huck Mag

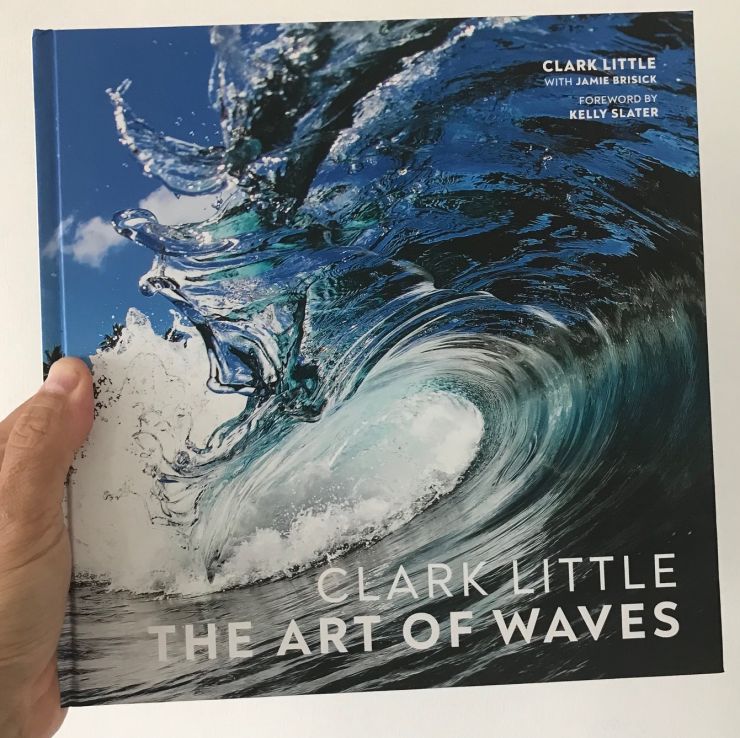

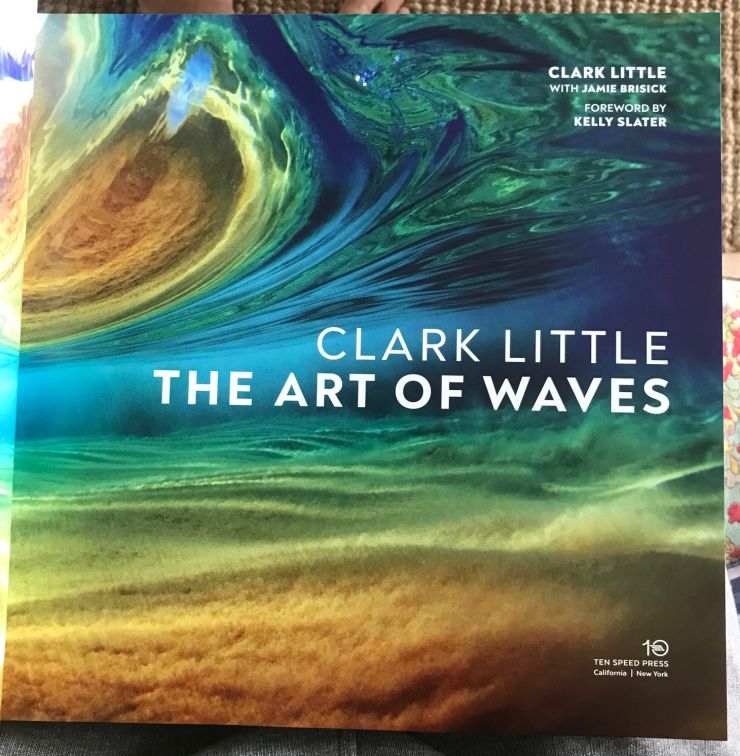

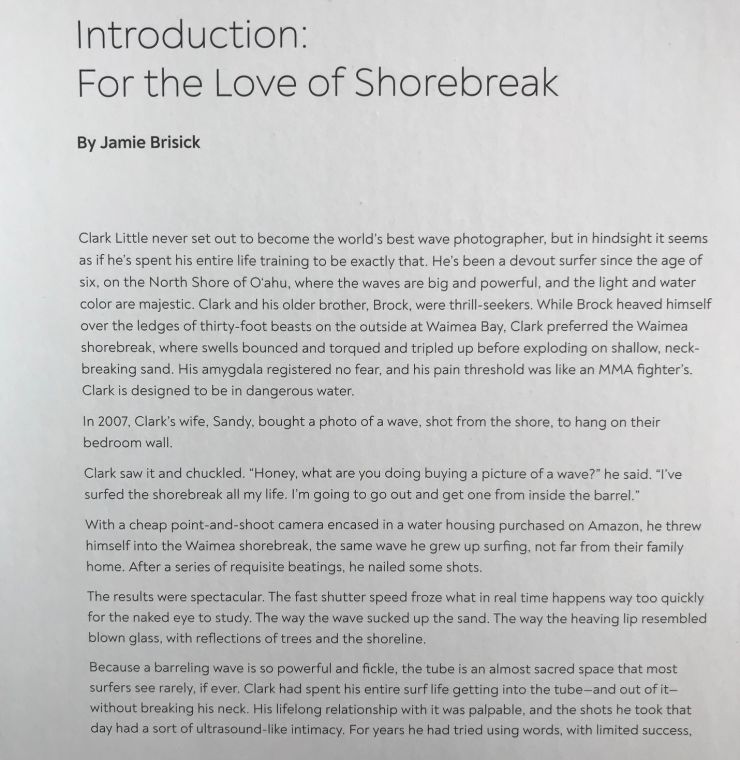

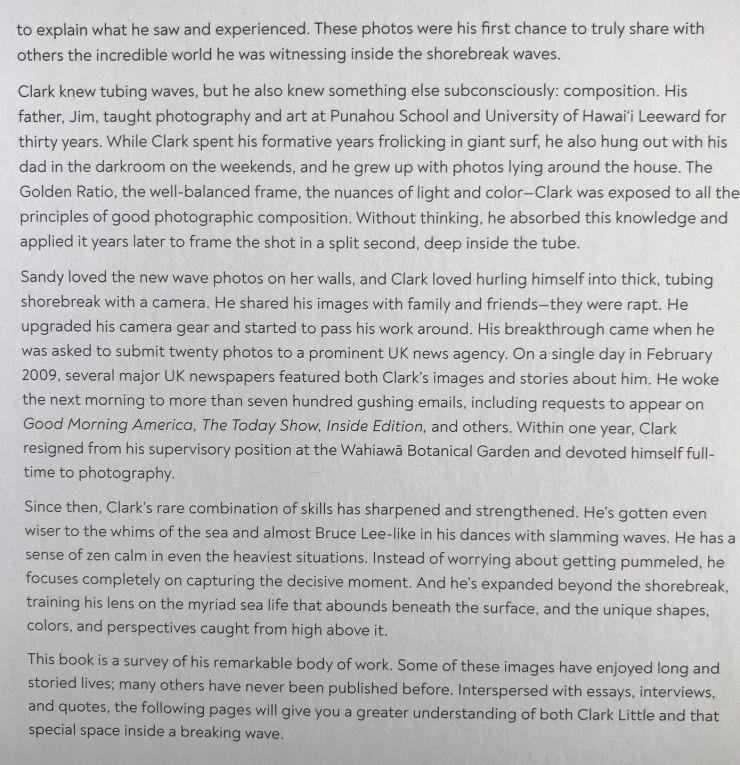

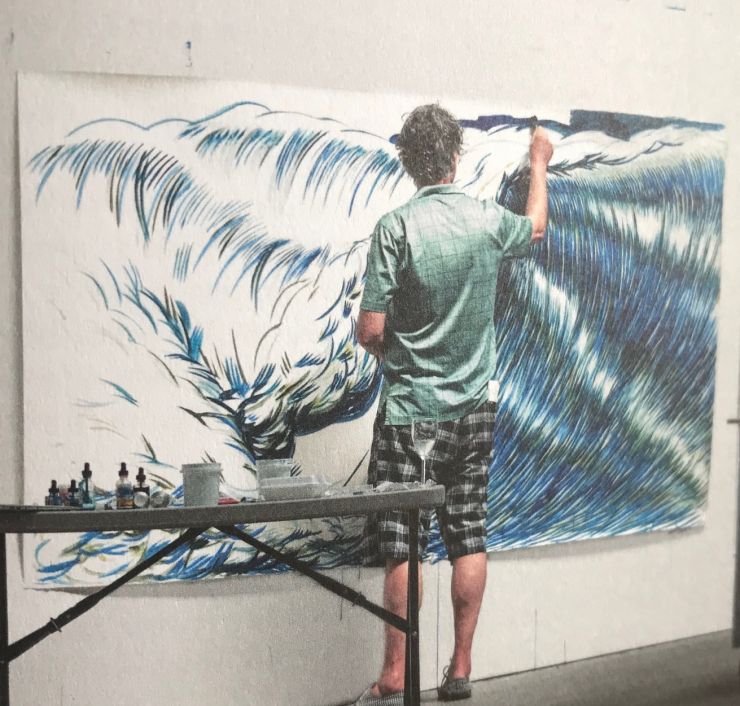

Clark Little: The Art of Waves

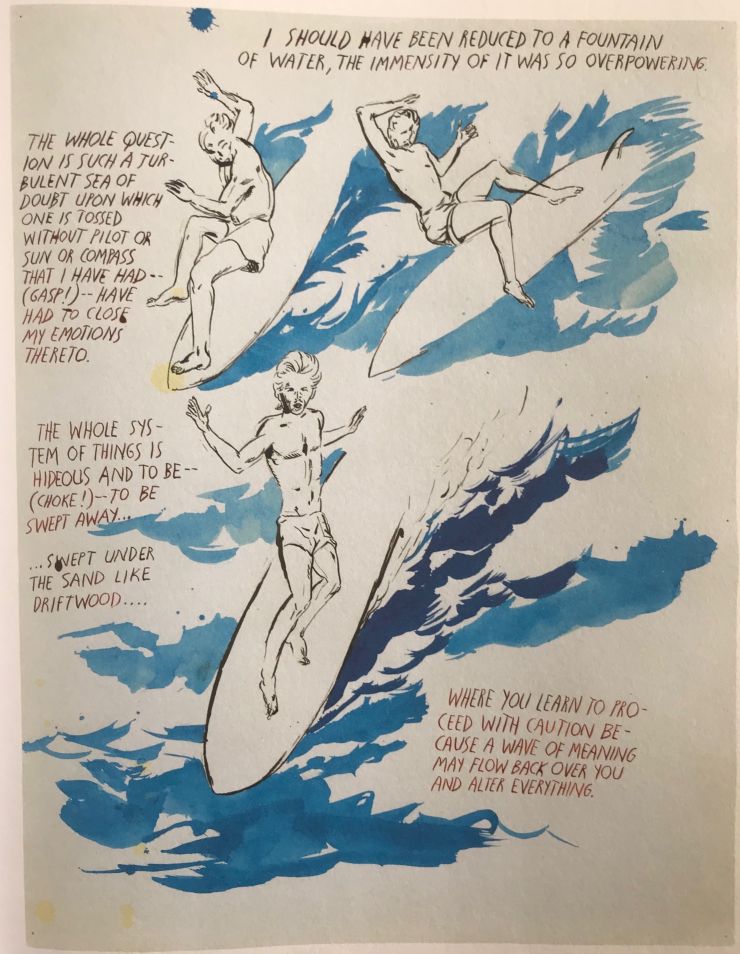

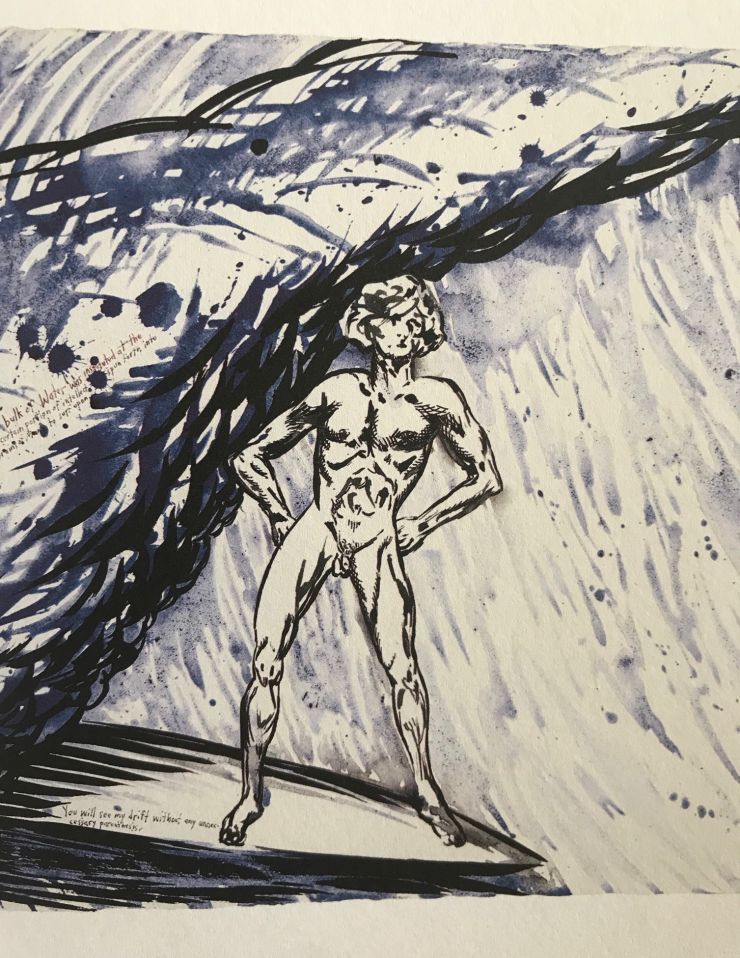

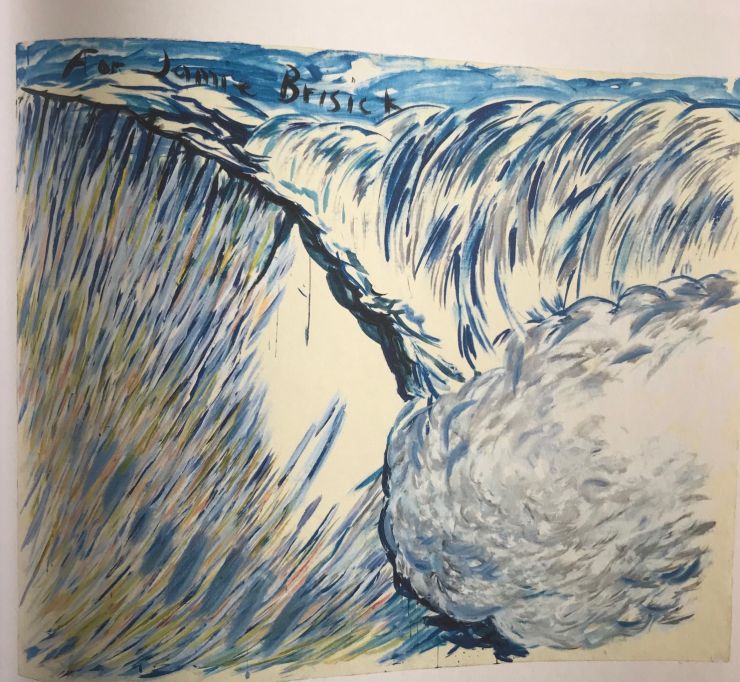

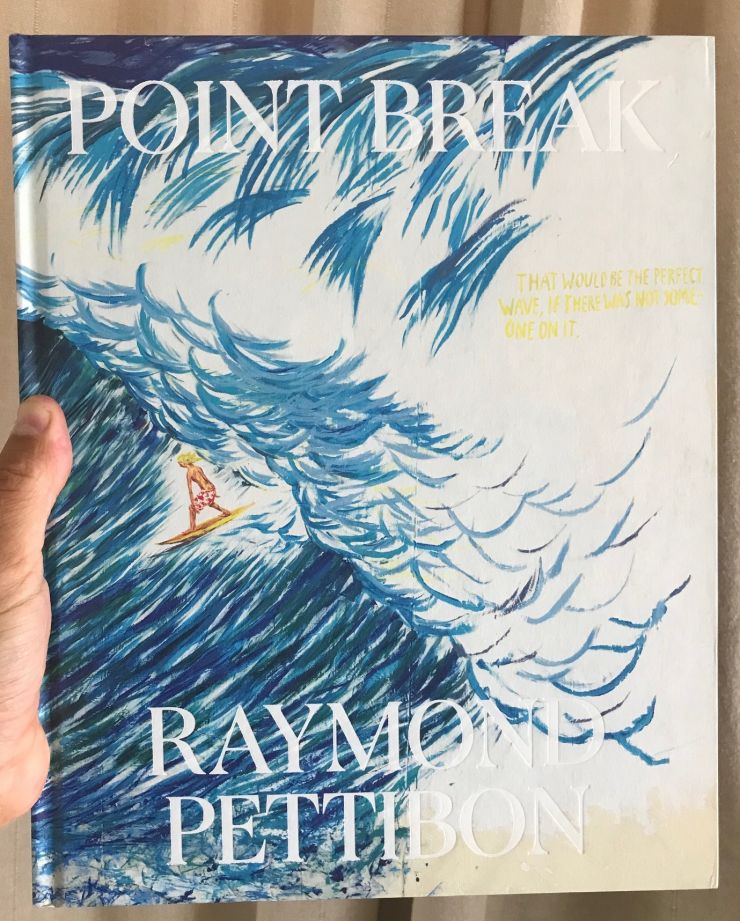

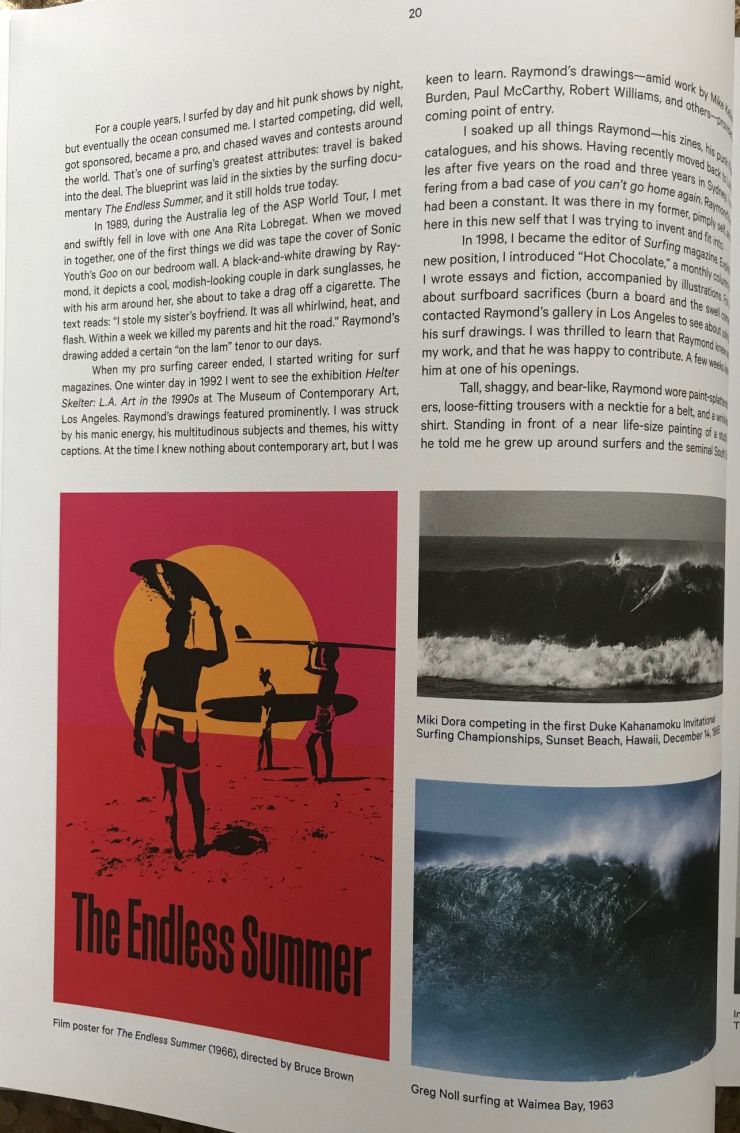

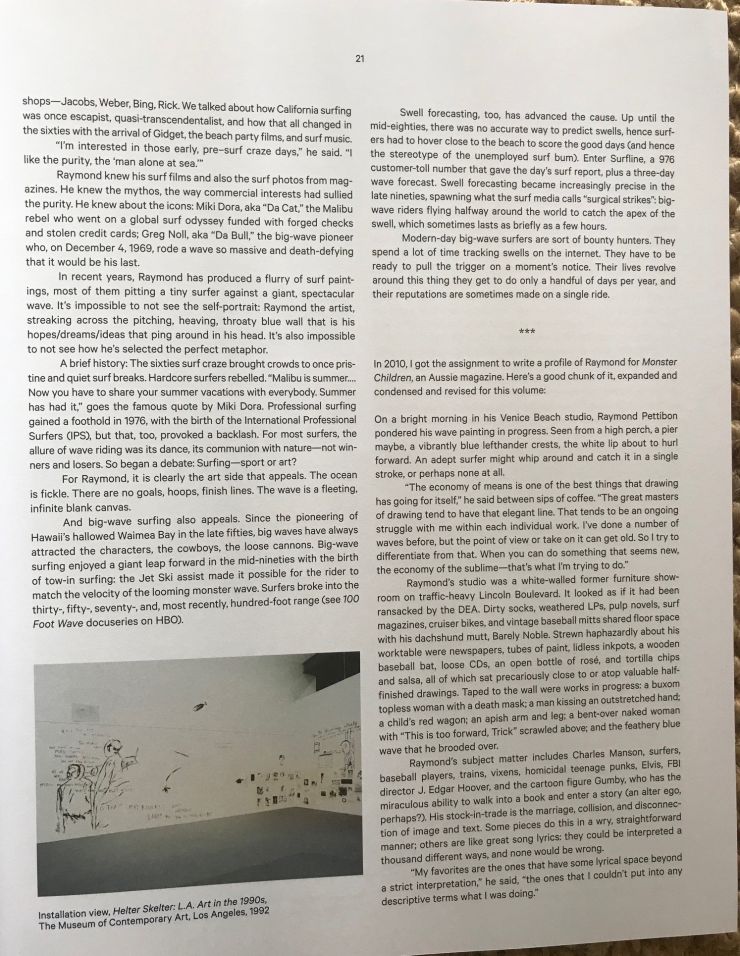

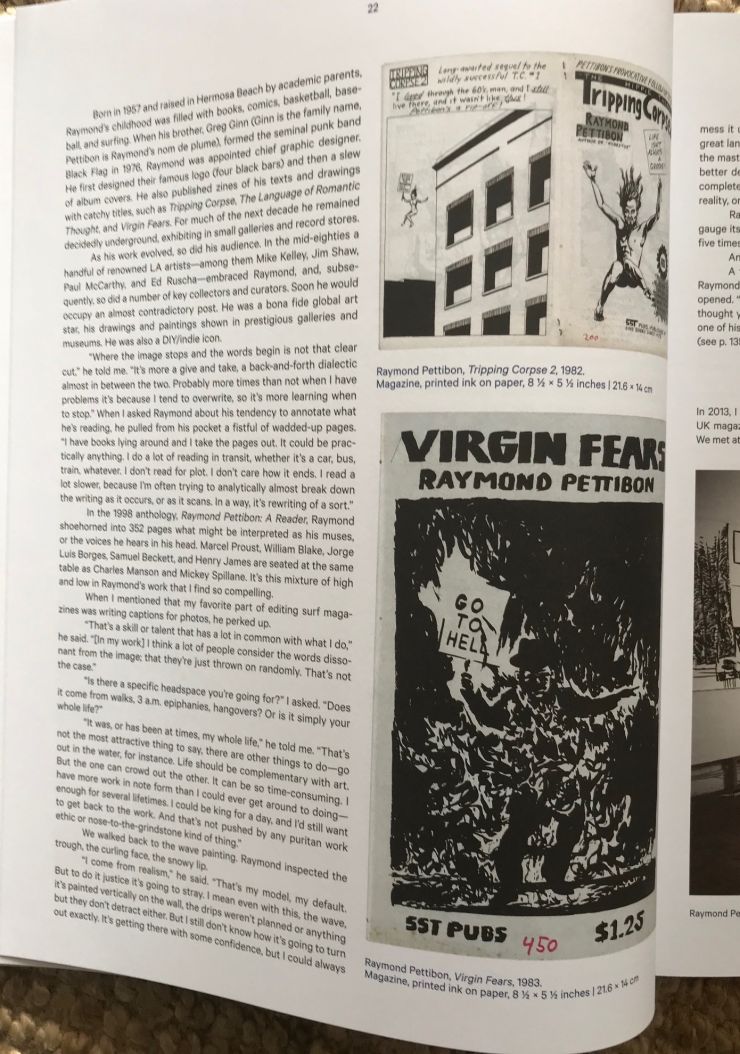

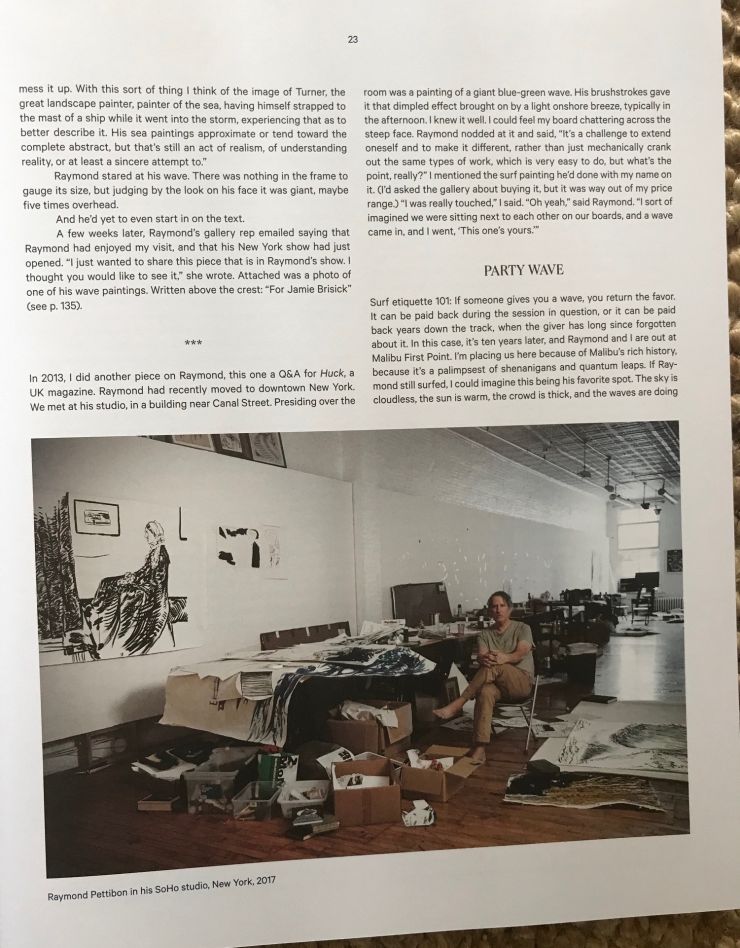

Raymond Pettibon’s “Point Break”

“When Life Revolved Around the Waves” - the North Shore in WSJ

Nearly Fossilized in the Dirt

We passed a pair of underwear, sun-bleached and nearly fossilized in the dirt. Further along was a bra, and then a shattered Jack Daniels bottle, and then the faded remains of a Trojan wrapper.

“Someone got laid,” said Kevin.

He said it with conviction, as if he was in on something that I wasn’t.

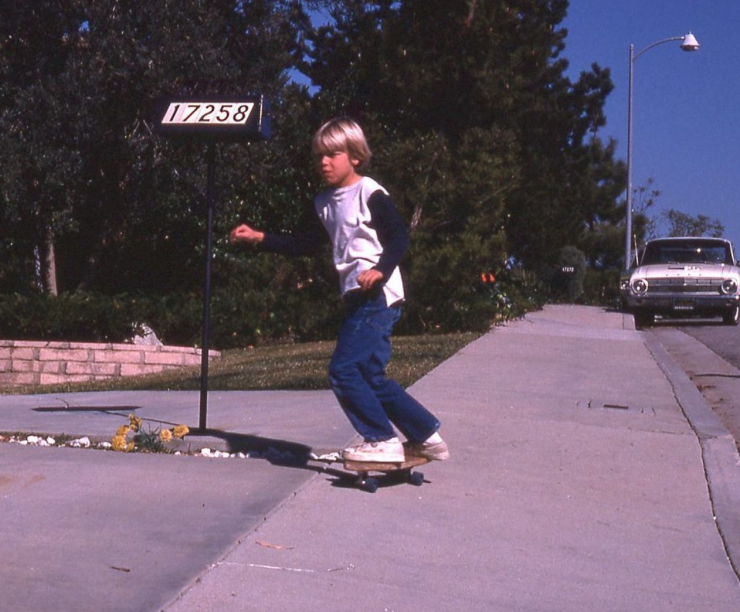

We climbed a crumbly hill that led out to a summit overlooking the whole of Westlake. You could see the cul de sacs, the man-made lake, the greenbelts, the tennis courts, the swimming pools, the stuff that we would soon come to know as “suburban mediocrity.”

“Looks like a bad idea,” said Kevin.

He unzipped his shorts and took a piss. I did the same.